Chapter 2 - Appraisal Process, Economic Areas, and the Approaches to Value

The Appraisal Process and Land Valuation

Land should be valued by incorporating the steps of the appraisal process. In this way, all sources of appraisal information will have been explored and the final estimate of value will reflect a justifiable and defensible conclusion based on this appraisal information.

The steps in the appraisal process are as follows:

- Definition of the problem

- Preliminary survey and planning

- Data collection and analysis

- Application of the approaches to value

- Reconciliation of value estimates

- Final estimate of value

Definition of the Problem

Beginning the land valuation process requires that the appraiser define the problem, the solution to which is the objective of the appraisal. In defining the problem, the appraiser needs to determine the following, prior to beginning the appraisal:

- Identification of the subject property or properties

- Property rights involved

- Date of appraisal and assessment date and level of value

- Purpose and function of the appraisal

- Definition of value

Identification of the Subject Property

Identification of the property can be provided by a street address, legal description or parcel identification number. Additional information about property identification may be found in ARL Volume 2, Administrative and Assessment Procedures, Chapter 13, Land Identification and Real Property Descriptions, and Chapter 14, Assessment Mapping and Parcel Identification.

Property Rights Involved

Colorado statute § 39-1-103(5)(a), C.R.S., requires that the fee simple estate be valued for property tax purposes. This requirement is confirmed by § 39-1-106, C.R.S., - the Unit Assessment Rule. Market value of the fee simple estate should reflect market assumptions, including market rent, market expenses, and market occupancy. For most real property interests, Colorado assessors are required by §§ 39-1-106 and 39-5-102(1), C.R.S., to assess land to the owner of record. The appraiser should be aware that fractional ownership interests in land may exist and those interests should be identified during the definition of the problem step in the appraisal process.

Possessory interests in exempt land may exist. Refer to Chapter 7, Special Issues in Valuation, under Assessment of Possessory Interest, for classification and valuation procedures for possessory interests.

Date of Appraisal and Assessment Date

The date of appraisal is June 30 of the year preceding the year of general reappraisal. All applicable approaches to appraisal must be trended or adjusted to this date.

Colorado statute § 39-1-105, C.R.S., provides that the date of assessment is to be January 1 each year and that all property is to be listed as it exists in the county where it is located on the assessment date.

To distinguish between the two dates, the assessment date refers to the date upon which property situs (location), taxable status, and the property's physical characteristics are established for that assessment year, while the appraisal date refers to the date upon which the valuation of the property is based or otherwise adjusted or trended.

For additional information on the appraisal date and the data collection period, please refer to Chapter 3, Sales Confirmation and Stratification.

Purpose and Function of the Appraisal

The purpose of the land appraisal is to estimate value. The function of the land appraisal refers to the reason that the appraisal was created, i.e., as a basis for property taxation.

Definition of Value

Other than very generally in §§ 39-1-103(5)(a) and 104(10.2)(d), C.R.S., Colorado statutes do not provide a specific definition of actual value. However, there are a number of Colorado court cases that mention actual value and market value. In Fellows v. Grand Junction Sugar Co., 78 Colo. 393, 242 P. 635 (1925), the court concluded that "In determining ‘fair value’ or ‘actual value’, market value is usually taken as the measure, because it is most likely to be just and least difficult of ascertainment." Other Colorado cases such as Colorado & Utah Coal Co. v. Rorex, 149 Colo. 502, 369 P.2d 796 (1962) and May Stores Shopping Centers, Inc. v. Shoemaker, 151 Colo. 100, 376 P.2d 679 (1962) mention market value and attempt to define it.

The definition of market value developed by the Appraisal Institute is based on California case law: Sacramento Southern R.R. Co. v. Heilbron, 156 Cal. 408, 104 P. 979 (1909).

The Appraisal Institute market value definition derived from the above case is as follows:

"The most probable price, as of a specified date, in cash, or in terms equivalent to cash, or in other precisely revealed terms, for which the specified property rights should sell after reasonable exposure in a competitive market under all conditions requisite to a fair sale, with the buyer and seller each acting prudently, knowledgeably, and for self-interest, and assuming that neither is under undue duress."

Preliminary Survey and Planning

After definition of the appraisal problem, the appraiser must begin development of a plan for the appraisal. In developing the plan, an analysis of property uses must be completed.

There are basically two steps in preliminary survey and planning:

- Determination of the use of the property and an analysis of how actual use of the property relates to its highest and best use

- Development of the plan for the appraisal

Use Determination and Highest and Best Use

In developing a good land valuation program, the assessor must correctly classify land. The primary criterion for classification is the actual use of the land on the assessment date. When actual use cannot be determined through physical inspection, the property owner should be contacted. The assessor may also consider such things as zoning or use restrictions, historical use, or consistent use, in determining land use. When unable to determine actual use, the assessor may consider the land’s most probable use, as of the assessment date, based on the best information available.

Proper classification is also very important for abstract purposes. To ensure that each parcel has the proper coding, and for classification descriptions, refer to ARL Volume 2, Administrative and Assessment Procedures, Chapter 6, Property Classification Guidelines and Assessment Percentages. After reviewing the instructions and codes, land appraisers should enter the county's appropriate classification and subclassification code on each parcel's property record.

Proper land classification is essential in order to establish how the property is to be valued. Classification, based on actual use, should not be confused with determining value. Colorado statutes require that certain types of land be valued using variations on, or elimination of, one or more of the three approaches, i.e., the cost, market, or income approach, to value. Examples of this requirement would be in the valuation of residential improved land, agricultural land, oil and gas leaseholds and lands, and producing mines. Unless otherwise directed by law, the three approaches to value should be considered.

Valuation for ad valorem property taxation should be based on a property’s highest and best use. The requirement of valuing property at its highest and best use was affirmed by the Colorado Supreme Court in Board of Assessment Appeals, et al, v. Colorado Arlberg Club, 762 P.2d 146 (Colo. 1988). In that case the court concluded that “reasonable future use is relevant to a property’s current market value for tax assessment purposes.” The court further noted “our statute does not preclude consideration of future uses” and it quoted the American Institute of Real Estate Appraisers, referencing The Appraisal of Real Estate 33, 1983, 8th Edition, “In the market, the current value of a property is…based on what market participants perceive to be the future benefits of acquisition.” Reasonable future use is based on the actions and expectations of the market, and is consistent with the highest and best use concept that requires use to be physically possible, legally permissible, financially feasible, and maximally productive.

Economic Unit Analysis (AKA, Tie-Back Parcels)

Colorado Statute 39-5-104, titled Valuation of Property, states that “When a single structure, used for a single purpose, is located on more than one town or city lot, the entire land area shall be appraised and valued as a single property.” Also, the statute requires that these parcels are under the same ownership and are adjoining. This statute applies the economic unit concept as explained in the Dictionary of Real Estate Appraisal, 7th ed.: “A combination of parcels in which land and improvements are used for mutual economic benefit.” The Dictionary also notes that “identification of economic units is essential in highest and best use analysis.” A highest and best use analysis is the foundation of all appraisal and is the first step in identifying an economic unit. The Highest and Best Use analysis will answer the question whether an out parcel is part of the economic unit or instead is excess or surplus land. If it is determined that an out parcel is excess or surplus land, then it should be valued separate from the economic unit. On the other hand, if the out parcel is determined to be part of the economic unit, then its value is included as part of that unit. The overarching concept here is that these properties are valued as a unit rather than as the sum of the individual parcels that make up the economic unit. However for ad valorem appraisal a separate value must be assigned to each parcel that makes up the economic unit. Guidance from the Dictionary is only that each parcel must make a positive economic contribution to the unit. For fee appraisal this distinction is typically not an issue as the appraiser’s assignment is to value the economic unit. A common example of this situation is shopping centers that include out parcels that provide access or the required parking to meet market standards. (These out parcels are often referred to as tie-back parcels.) In this situation the market value of the shopping center, the economic unit, is established by consideration of the three approaches to value. Although most of this value is with the parent parcel, value must be assigned to each out parcel. A corresponding reduction must be made to the total market value of the center as reflected in the parent parcel, so that the economic unit is not overvalued.

Development of an Appraisal Plan

Development of a plan, especially when undertaking a mass appraisal of land, is essential in order to use available resources at maximum efficiency. Planning for an appraisal involves the following:

- Consider, determine, and document which approaches to value will be most appropriate.

In considering, determining, and documenting which valuation approach or approaches should be used, Colorado case law should be referenced.

Montrose Properties, LTD., et al., v. Colorado Board of Assessment Appeals, et al., 738 P.2d 396 (Colo. App. 1987) affirms § 39-1-103(5)(a), C.R.S., and defines the assessor's "appropriate consideration" of all required approaches to value. The court concluded that "appropriate consideration" was used by an assessor when the assessor decided that insufficient information precluded the use and calculation of one or more of the required approaches. The court reasoned appropriate consideration was used in determining the approach(es) that were not applicable. The need for appropriate consideration of the three approaches was affirmed by the Colorado Supreme Court in Board of Assessment Appeals, et al., v. Sonnenberg, 797 P.2d 27 (Colo. 1990).

Transamerica Realty Corporation v. Clifton, et al., 817 P.2d 1049 (Colo. App. 1991) requires the assessor to provide evidence to support adequate documentation of the values established for all applicable approaches to appraisal. Insufficient time is not a reasonable excuse for failure to consider the applicable approaches to appraisal.

These requirements have considerable current impact due to § 20 of article X of the Colorado Constitution removing the presumption of correctness from the assessor's values. Beginning January 1, 1993, valuation issues shall be decided based on the preponderance of the evidence.

- Determine what type of appraisal data must be gathered and what data sources are available.

- Determine resource requirements and allocate existing resources in a manner to complete a quality appraisal.

- Estimate the budget cost for the appraisal. If budgets have been previously set and additional funds are not available, the appraisal plan must be redrawn to fit into existing budget constraints.

Specific information on development of an appraisal plan may be found in ARL Volume 2, Administrative and Assessment Procedures, Chapter 2, Assessment Operations.

Data Collection and Analysis

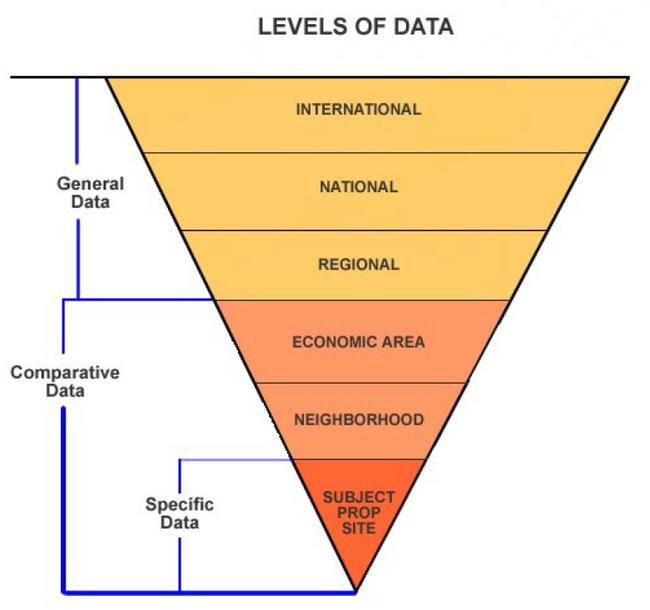

Appraisal data that will be collected and analyzed will fall into one of three categories:

- General

- Specific

- Comparative

General data is an overall category that pertains to information about the four forces (physical, economic, governmental and social) originating outside a subject property and those forces' influence on that property's value. General data provides a background basis for analysis of international, national, and regional trends that affect value.

Examples of general data would be U.S. Census publications, U.S. Labor Department employment statistics, and Colorado Division of Housing information on construction costs and housing starts.

Specific data pertains primarily to information about the site. Examples of specific data would be title and recorded information such as legal description, special assessments, zoning, easements, other public restrictions, and physical information about the site.

Comparative data consists of cost, sales, and income information on individual properties. When properly screened and confirmed, comparative data is used directly in the cost, market, and income approaches to valuing the subject property.

Examples of comparative data are vacant land sales collected within the statutory data collection period as stated in § 39-1-104(10.2), C.R.S., development costs for comparable subdivisions, and economic rental rates.

Refer to the following diagram for a graphic representation of how general, specific, and comparative data are collected for various geographic areas.

Survey of Appraisal Information Sources

Data sources of appraisal information may be divided into two categories.

- Public records

- Private sources

The major sources of public records are found in the county courthouse.

The local county clerk is a source of information on the following:

- Documentary fee information for land sales

- "Real Property Transfer Declarations" (Form TD-1000) for deeds requiring documentary fees and recorded after July 1, 1989. “Manufactured Home Transfer Declarations" for titled manufactured homes that are conveyed after July 1, 2009. These are confidential

- Copies of recorded leases

- Land descriptions from recorded plats

- Other general data about the county and cities within the county

The local planning office is a good source of information on the following:

- Zoning

- Building codes

- Traffic patterns

- Water and sewer availability

- Other important data about the property

Private sources include the following:

- A subscription to the Multiple Listing Service sold book*

- Real estate agents' records

- Publications of all types

- Media advertising

- The local Chamber of Commerce office

- Other appraisers

- Title companies

- Mortgage banks

- Property managers

- University or college studies

- Other similar sources

*Provided by the local Realtor's Association.

Neighborhoods and Economic Areas

The following subsections refer to the development of neighborhoods and economic areas.

Economic Base Analysis

Economic base analysis is the evaluation of the supply of products produced and services delivered in a given area and the demand for these products in the local, regional, national, and international markets.

In the context of the appraisal process, the supply of and demand for various goods and services affect the value of real estate in the smallest unit of analysis: the neighborhood.

Neighborhoods, as used in the appraisal process, are an essential part of valuing property. Neighborhoods are created through the collection, grouping, and analysis of data. The correct establishment and use of neighborhoods must be a part of every assessor's job.

Social, environmental, economic, and governmental forces directly affect the subject property within a neighborhood. In single-property appraisal, neighborhood analysis should begin with the definition of a neighborhood and proceed to the analysis and discussion of the relevant forces influencing the subject property at this level. The neighborhood boundary should be described in detail and its historical significance explained.

A neighborhood has direct and immediate effects on value. A neighborhood is defined by natural, man-made, or political boundaries and is established by a commonalty based on land uses, types and age of buildings or population, the desire for homogeneity, or similar factors.

Each neighborhood may be characterized as being in a stage of growth, stability, decline, or revitalization. The growth period is a time of development and construction. In the period of stability, or equilibrium, the forces of supply and demand are about equal. The period of decline reflects diminishing demand or desirability. During decline, general property use may change. Declining neighborhoods may become economically desirable again and experience renewal, reorganization, rebuilding, or restoration, marked by modernization and increasing demand.

The appraiser must analyze whether a particular neighborhood is in a period of growth, stability, decline, or revitalization and predict changes that will affect future use and value.

In mass appraisal applications, neighborhood information can be useful for comparing or combining neighborhoods or for developing neighborhood ratings, which are introduced as adjustments in mass appraisal models.

Byrl N. Boyce and William N. Kinard, authors of Appraising Real Property, 1984, Lexington Books, pp. 103-104 state:

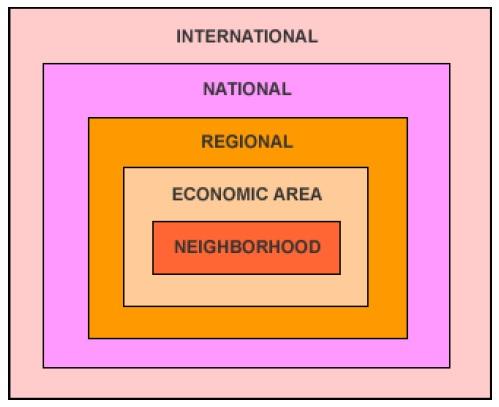

The farther removed from the subject property the market level is, the less direct and immediate will be the effect of any change on the subject property and its value. Thus, international market forces (such as oil prices or the price of gold) or national market factors (such as the prime rate of interest or the purchasing power of the dollar) create general market conditions within which real estate values and prices are set and fluctuate along with other prices or values.

Further:

Regional market forces (such as area employment and construction volume) have a closer, more nearly direct, more nearly immediate impact on the value of the subject property and of properties which are competitive with it. Local or community market forces (e.g., local population, employment, incomes, and competition) are even closer to the subject property and influence its value even more directly. Closest of all is the neighborhood level, where any change tends to have a direct and immediate impact on the value of the subject property.

In looking at neighborhoods, the first matter that should be examined is the nature of the data involved. Data can be classified in various groupings. While some data crosses group boundaries, there are certain characteristics each group possesses that distinguish it from the others.

Examples:

| International Data | Oil Prices |

|---|---|

| National Data | Prime Interest Rate |

| Regional Data | Area Employment |

| Economic Area Data | Local Interest Rate |

| Neighborhood Data | Northwood Subdivision |

The first three groups, international, national, and regional, do not have a direct impact on a county level, with the exception of special purpose properties, e.g., breweries, mines, and cement plants.

Economic Areas

An economic area is a geographic area, typically encompassing a group of neighborhoods, defined on the basis that the properties within its boundaries are more or less equally subject to a set of one or more economic forces that largely determine the value of the properties in question. Economic areas can contain a neighborhood consisting of single family homes as well as a neighborhood consisting of multi-family properties as long as each neighborhood is subject to the same forces.

A neighborhood may be defined as the immediate environment of a subject property that has a direct and immediate impact on its value. The terms "work area" and "modeling area" are frequently associated with "neighborhood" and are considered synonymous.

Neighborhood boundaries should be used primarily as a tool when determining "similar values for similar properties in similar areas." The neighborhoods should then be combined into economic areas for sales ratio analysis, statistical analysis, or any other market data tests.

Neighborhood and, subsequently, economic area analyses are required because what occurs in the economic area has a direct and immediate impact on the values of the properties within it.

Additional terms frequently used in appraisal, but not considered synonymous to the term economic area are "subdivision," "filings," "absorption rate," and "approved plat." These terms are specific to other procedures such as "land use" or "vacant land present worth" and are not to be confused with economic areas.

Economic Area Analysis

An economic area exhibits a greater degree of uniformity than a larger area. Obviously, no group of inhabitants, buildings, or business enterprises can possess identical features or attributes, but an economic area is perceived to be relatively uniform. In addition, the neighborhoods that are grouped within the economic areas are equally subject to the same economic forces.

Economic area boundaries identify the physical area that influences the value of a subject property. Economic areas commonly contain properties of different use and types.

Therefore, the purpose in developing neighborhood boundaries is to evaluate a specific class or subclass of property within a larger economic area boundary. Neighborhoods are grouped into economic areas for purposes of statistical analysis.

In developing economic area boundaries the four forces that affect value need to be considered:

- Physical/Environmental

- Economic

- Governmental

- Social

The interaction of all the forces influences the value of every parcel of real estate in the market. Although the four forces are discussed separately, they work together to create, maintain, modify, or destroy value.

Physical/Environmental Force

By using maps and other geographic information, the appraiser can identify physical boundaries and where changes in these boundaries occur. By driving around a defined economic area, the appraiser can note the similarity in land use, structures, styles, and maintenance of the area.

Location is the most important factor of the physical forces and it has the greatest impact on valuation. Other physical factors that may be analyzed in developing neighborhood boundaries and, subsequently, economic areas include the following:

- Topography and soil

- Natural barriers to future development, such as rivers, mountains, and lakes

- Primary transportation systems, including federal and state highway systems, railroads, and airports

- The nature and desirability of the immediate area surrounding a property

Economic Force

Economic force considerations relate to the financial capacity of economic area occupants to rent or to own property, to maintain it in an attractive and desirable condition, and to renovate or rehabilitate it when needed.

Economic factors that determine the ability of residents or tenants to own and maintain properties in a competitive market include mortgage interest rates, income levels, and ownership and rental information. These economic factors should be listed to allow analysis of their contribution to value.

The economic characteristics of residents and the physical characteristics of individual properties, their neighborhood, and the larger economic area may indicate the relative financial strength of area occupants and how this strength is reflected in economic area development and upkeep.

Market characteristics considered in the analysis of economic forces include the following:

- Employment, wage levels, and industrial expansion

- The economic base for the region

- Community price levels

- The cost and availability of mortgage credit

- Availability of vacant and improved properties and new development under construction or being planned

- Occupancy rates

- The rental and price patterns of existing properties

- Construction costs

Governmental Force

Governmental actions and regulations also act as a force to influence the character of economic areas. Government factors should be listed and analyzed for their contribution to value. These government factors include local laws, regulations, taxes, and restrictions that affect neighborhoods and their economic areas by influencing the type of occupants that will be found in the area.

The government provides many facilities and services that influence and control land use patterns. The following should be listed and analyzed for possible contributions to value:

- Public services such as fire and police protection, utilities, refuse collection, and transportation networks

- Local zoning, building codes, and health codes, especially those that obstruct or support land use

- National, state, and local fiscal policies

- Special legislation that influences general property values, e.g., rent control laws, restrictions on forms of ownership such as condominiums and timeshare arrangements, homestead exemption laws, environmental legislation regulating new developments, and legislation affecting the types of loans, loan terms, and investment powers of mortgage lending institutions

- Tax burdens relative to the services provided, and special assessments

Social Force

The social force is exerted primarily through social attitudes and demographics (population characteristics) including changes in total population, the rate of family formations and dissolutions, and age distributions. An economic area's character and real property values are strongly influenced by the residents who live and work there.

Social factors are closely tied to the life cycles of neighborhoods and their economic areas. People are attracted to certain economic areas by life style, services available, price range, and convenience.

According to The Appraisal of Real Estate, 2013, 14th Edition, Appraisal Institute, page 167 (Paraphrased):

The important social characteristics that the market considers in neighborhood analysis

include:

- Population density, particularly important in commercial neighborhoods

- Occupant skill levels, particularly important in industrial or high-technology districts

- Occupant age levels, particularly important in residential neighborhoods

- Household size

- Occupant employment status, including types of unemployment

- Extent or absence of crime

- Extent or absence of litter

- Quality and availability of educational, medical, social, recreational, cultural, and commercial services

- Community or neighborhood organizations, e.g., improvement associations, block clubs, crime watch groups

Development of Economic Areas

Differences in economic area desirability often coincide with natural barriers, major streets, subdivision lines, and housing style. These differences are usually reflected in the price of land, trends in property values, and the prices for which houses of seemingly comparable physical characteristics tend to sell.

Before economic area boundaries are defined, neighborhoods should be developed for each class of property. It is possible for residential, commercial, industrial, and vacant land neighborhood boundaries to overlap.

However, neighborhood subclass boundaries cannot overlap within the same subclass. For example, the neighborhood boundary for NBHD 1, consisting of single family homes, cannot overlap into NBHD 2, which also consists of single family homes. However if NBHD 1 and NBHD 2 are equally subject to the four forces, they can both be in the same economic area.

Stratifying a class of property into homogeneous subclasses can enable the assessor to develop accurate values for property. For example, if condominium values are based only on condominium sales, the values placed on unsold condominium properties will be more reflective of the condominium market than would be the case if these values were based on a composite of all residential sales. It is also possible to stratify the subclasses of property into age, style, construction type, and quality groupings. However, the appropriate level of stratification is dependent on the number of available qualified sales and whether the number of qualified sales allows a statistically reliable estimate of value.

The development of economic areas begins first by considering the physical, economic, governmental, and social forces affecting value within neighborhoods and by considering property subclass homogeneity as discussed above. The identification of each economic area boundary can then be completed through the completion of the following steps:

- Inspect the physical characteristics of neighborhoods. Drive around the region to develop a visual sense of possible groupings of neighborhoods into economic areas, noting the degree of similarity in land uses, types of structures, architectural designs, quality, and condition. On a map of the area, note the points where these characteristics show perceptible changes and mark any physical barriers such as streets, hills, rivers, and railroads that coincide with the changes. These notes and marks establish preliminary economic area boundaries.

- Compare the preliminary economic area boundaries against the socioeconomic characteristics of the area's population and make adjustments to the boundaries taking into consideration the economic, governmental, and social forces affecting value, as well as, elements of homogeneity. Reliable data may be obtained from local chambers of commerce, universities, and research organizations. Additional information may be gathered from informal interviews with property owners, business persons, real estate professionals, and community representatives to determine the extent of an economic area.

- Review and analyze sales data within each adjusted economic area by plotting sales prices per square foot (or other unit of comparison), coded by subclass, within the adjusted economic area boundaries on a property sales map and/or by performing statistical tests such as sales ratio studies for the economic area with sales ratios coded by neighborhood. Make final adjustments to economic area boundaries with the understanding that these boundaries may change along with changes in the economic forces and factors in subsequent reappraisal years.

Examples of market analysis procedures can be found in Property Appraisal and Assessment Administration, 1990, and the Standard on Ratio Studies, 2010, both published by the International Association of Assessing Officers.

Land Subclass Analysis

Residential Land

Residential land values are based on desirability, scarcity, surroundings, restrictions, utilities, and location. The more desirable the location, the more valuable the land. Desirability is stimulated by the factors of surroundings, land use restrictions, utilities, availability of transportation, shopping facilities, schools, and churches.

Commercial Land

Commercial lands are primarily bought as investments or as income producing properties. The value of this type of land is based on the need for commercial goods and services in the economic area, availability of suitable sites to accommodate those goods and services, and reasonable access to the land by both the owner/user and potential purchasers of goods and services.

Industrial Land

Industrial lands are subject to highly specialized and intensive use analyses that are wholly dependent upon each individual owner's requirements. Industrial properties rarely sell on the open competitive market as other than unimproved sites. Each industrial property requires special analysis because of the land's individual characteristics. Each site should be studied in detail as to use, topography, shape, utility, site improvements, industrial capacity, zoning, location in relation to transportation, proximity of the labor market, and accessibility to the customer market.

"Other Agricultural" Land

Agricultural land valuations are based upon productivity formulas contained in the Colorado Constitution, statutes, and Division policy. Refer to Chapter 5, Valuation of Agricultural Lands.

"Other agricultural" lands, that are sometimes referred to as agribusiness properties when improvements are built, are primarily bought as income producing properties. As required by § 39-1-102(1.6)(b), C.R.S., the actual value of this type of land is to be based on the three approaches to appraisal based on its actual use on the assessment date. Comparison of sales of similar agribusiness properties must be used in the market approach. If the income approach is used to value this land, the income must be established based on a use similar to the actual use of the subject. This method differs from that used by the assessor to establish actual valuations of agricultural lands. Also, another difference is that personal property associated with "other agricultural" operations is not exempt. For a definition of exempt agricultural equipment refer to Chapter 5, Valuation of Agricultural Lands.

Natural Resource Leaseholds and Lands

Like industrial lands, natural resource lands are subject to highly specialized and intensive use analyses that are wholly dependent upon each individual owner's requirements. Natural resource properties rarely sell on the open competitive market. When properties are sold, they should be studied to determine if the sale price attributable to improvements and personal property can be isolated. Each natural resource property requires special analysis because the assessor's actual valuations of natural resource leaseholds and lands are, in part, established based upon statutory productivity formulas that may not reflect market value. Refer to Chapter 6, Valuation of Natural Resources.

Recommendations

The following procedures are recommended by the state board when establishing economic areas:

- Complete a written narrative describing the forces affecting the value of the properties within defined neighborhoods.

- Attach unique codes to all neighborhoods and appropriately code all properties in the county for computer access and for purposes of analysis.

- Indicate the number of properties within each neighborhood.

- Indicate the number of sales within each neighborhood.

- Draw preliminary economic area boundaries on a map by connecting the points where the physical characteristics of neighborhoods change.

- Through the analysis of economic forces and property subclass homogeneity, adjust preliminary economic area boundaries.

- Using sales prices per square foot, coded for subclass, and sales ratio analysis, with sales ratios coded by neighborhood, establish final economic areas. Physically draw final neighborhood boundaries on a map.

Requirements

Each county is required by the state board to complete the following:

- A physical map delineating economic areas resident in the county and the justification therefore. The State Board of Equalization's intent is written justification.

- The county must, through computerization, appraisal records, or other means, be able to identify each property within the economic areas.

For further information on economic area stratification, please refer to the following publications.

- Property Appraisal and Assessment Administration, 1990, International

Association of Assessing Officers. - Standard on Ratio Studies, 2010, International Association of

Assessing Officers-Assessment Standards Committee.

The Approaches to Value

Colorado statutes require that the cost, market (sales comparison), and income approaches to value be considered by the assessor when valuing land.

Within the framework of the three approaches, there are five accepted methods of valuation that may be used. These methods are as follows:

- Market (Sales Comparison) Approach

- Sales comparison method

The sales comparison method is the most reliable method of land valuation. This method first compares comparable vacant land parcels that have sold, during the selected data collection period, with subject properties, and then processes these sales prices into indicators of value by adjusting them for differences when compared to the subject properties. - Extraction or allocation method

The extraction or allocation methods are based on the principle that land has a defined relationship to the total property value. In the allocation method, a proportion of the total property value is allocated to the land. In the extraction method, the land value is extracted from sales of improved properties.

- Sales comparison method

- Cost Approach

- Anticipated use or developmental cost method

While there is no cost approach for vacant land, the anticipated use or developmental cost method is sometimes referred to as a cost method. It is used primarily where sales are limited and the land is in transition from agricultural use to residential or commercial use. The total anticipated development costs are subtracted from the anticipated sales price to indicate the value of the raw land.

- Anticipated use or developmental cost method

- Income Approach

- Capitalization of ground rent method

The capitalization of ground rent method employs the income approach. Income to the land is capitalized into an indication of value. This method is based on the premise that property value is based on the present worth of future benefits of property ownership. The market rent of the subject tract is estimated, a net income is calculated, and a capitalization rate selected. The net income is then capitalized into an indication of value by dividing the net income by the capitalization rate. - Residual (land) method

The land residual capitalization method involves estimating net income earned by a total property, establishing the cost of the building, and calculating and deducting from total net income the income attributable to the building. The remaining income attributable to the land is capitalized into an indication of value.

- Capitalization of ground rent method

Generally, the sales comparison method is preferred as it is the method that most closely approximates the effects of the market. In the absence of sales information, any of the other methods can be used to arrive at an indication of value. However, each of the other methods has drawbacks and the assessor should exercise caution when using them. Prior to using any of the above methods, vacant land sales must be discovered, collected, confirmed, and verified.

Sales Comparison Method

The sales comparison method compares the subject property to vacant land parcels that have sold within a designated time period. The comparable sales are adjusted for atypical financing, for time (date of sale), for location, and for other differences in physical characteristics between the sold property and the subject property. The adjusted sales prices are then correlated to a

value indicator representing the estimated sales price of the subject property. Application of this approach requires four steps:

- Discovery and confirmation of sales

- Selection of appropriate units of comparison

- Adjustments made to sales data

- Reconciliation of adjusted sales prices into a market indicator of the subject property's value

Assuming availability of data, this method will be the primary method used to determine land values.

Selection of Appropriate Units of Comparison

Selecting the proper unit of comparison in determining land values is critical to the use of the sales comparison method. For each zoning area or land subclass, the unit selected should be the one that best fits the market. The appraiser should always select the appropriate unit of comparison in terms of how property is bought and sold.

The most common units of comparison are as follows:

- Front foot

- Square foot

- Acres

- Site

- Units buildable

Front Foot

Use of the front foot as a unit of comparison is based upon the premise that frontage significantly contributes to value. A front foot unit is a strip of land one foot in width that lies parallel to the street and continues to the rear of the parcel. This unit is calculated by dividing the sales price of the parcel by the total frontage in feet. The front foot is generally used in the appraisal of residential and commercial land where parcels are of uniform depth, but differ in frontage.

Square Foot

The square foot unit of comparison is used for sites that typically sell for a given price per square foot of land area. Although this method is generally used for commercial sites, it can be used for residential and industrial land where the sites are irregular in shape or where frontage is not a critical factor in the salability of the parcel. This unit is calculated by dividing the sales price by the total square footage in the parcel. When using the square foot method for residential property, the assessor should be aware of the problem of surplus land valuation when the site is larger than a typical residential site. Adjustments may have to be made to account for the effect of the surplus land over and above the typical site. Refer to the Surplus Land Influence Adjustments topic found later in this section.

Acre

The acreage method is useful in the valuation of large residential tracts, rural and farm properties, large commercial tracts, and large industrial sites. Acres may be calculated by dividing the total square footage of a property by 43,560, the number of square feet in an acre.

Site

A site is defined as a parcel of land that has been improved or otherwise readied for its intended use. The site unit of comparison is used when the market does not indicate a significant difference in lot value when lots are of varying sizes. The site unit is becoming more prevalent and is found in residential subdivisions, cluster developments and planned-unit developments. In some cases, it may also be used in valuing sites located in commercial and industrial developments and parks.

Units Buildable

The unit of comparison based on units buildable is used when the market indicates that a parcel typically is sold by the number of units that are allowed to be built by zoning or land use regulations. This unit of comparison is calculated by dividing the sales price of each of the comparable sales by the number of units built on the comparable sale site. However, use of this unit of comparison is predicated on the fact that the comparable sales must have structures with the optimum number of units built as permitted by zoning regulations.

For example, apartment building sites may be sold on the basis of apartments buildable and parking lots may be sold on the basis of parking spaces rentable. The units buildable may be either a theoretical or an actual number of units. The probable number of units to be built may be different from the theoretical number permitted by zoning ordinances. Consideration should be given to market demand, set back limitations, dedications and deed restrictions, topography, height limitations, and other limiting factors.

Market Adjustments

Market adjustments may have to be made for the following:

- Adjustments for atypical financing such as below market seller financing, favorable assumed mortgages, or points paid by the seller

- Adjustments for time, i.e., trending sales to the appraisal date

- Adjustments for property characteristics, e.g., location, access, topography, soil conditions

Application of adjustments is the process of adjusting differences in the comparable sales so that they become as similar as possible to the subject property. All adjustments must be applied to the sales prices of the comparable properties. The adjusted sales prices then become indicators of value for the subject property. It is always better to adjust sales than to delete sales from the analysis. This is especially true if the number of qualified sales is limited. It is also better to gather sales from the same economic area over the full 60 months before using sales that will require a location adjustment.

Adjustment for Financing

Financing adjustments convert the sale price to current actual or market value on the date of sale. Seller participation, where financing rates are not available to the general public, and assumed leases are examples of situations specific to particular properties where sales adjustments for financing might be considered.

Adjustments for financing are rarely used in valuing property for ad valorem purposes. If a financing adjustment appears to be necessary, extreme caution should be applied when developing the financing adjustment. An example of developing adjustments for financing is shown below.

Example:

Adjustment for Financing - Below Market Interest Rate Secured

| Total Sales Price (Documentary Fee) | $12,000 |

|---|---|

| Down Payment | - $500 |

| Principal Financed | $11,500 |

| Term | 10 yrs |

| Contract rate of interest | 9% |

| Market rate of interest | 12% |

| Amortization | monthly |

| Contract Payment (9%, 10 yrs) (Column 6, Compound Interest Table) $11,500 X 0.012668 | $145.68 |

| Value of Loan (12%, 10 yrs) (Column 5, Compound Interest Table) $145.68 X 69.700522 | $10,154 |

| Down Payment (Added back in) | + $500 |

| Total Adjusted Sales Price | $10,654 |

| Rounded | $10,700 |

Note: The example above uses monthly compound interest tables, which can be found in published compound interest table listings. A good reference for complete compound interest tables is the Appraisal Institute's, Capitalization Theory and Techniques Study Guide. The study guide can be purchased by contacting the Appraisal Institute in Chicago.

The text, Property Assessment Valuation, Third Edition, International Association of Assessing Officers, Kansas City, 2010, contains only annual compound interest tables. Monthly and annual compound interest factors also can be calculated using business financial calculators.

Sales should only be adjusted for financing when both of the following circumstances exist and complete documentation requisite to the sale is available:

- The seller participates in the financing of the property to enhance its sale to the buyer, i.e., the seller does not receive the full cash proceeds from the sale at time of sale.

- The financing terms offered to and accepted by the buyer are not currently available in the open market.

The preferred method for making any market adjustment to a sale is by paired sales analysis following confirmation of the sales. A comprehensive sales confirmation program is essential for development of financing adjustments. It should be emphasized that selling prices adjusted for financing are merely value indicators and may not represent actual market value. Therefore, financing adjustments are to be used with extreme caution.

Measuring and Testing the Accuracy of Financing Adjustments

After developing adjustments for financing, the accuracy and validity of the adjustments need to be tested. Sales that have been adjusted for financing should be separately stratified for statistical analysis and the setting of values.

Sales, in which the seller receives the full sale proceeds in cash, either by way of a financial institution or directly from the buyer depending on the market, typically are the best measure of accuracy. Through sales ratio analysis, these sales will validate the financing adjustments made to the sale price if their median sales ratio compares favorably to that of the adjusted selling prices.

Through sales ratio analysis, re-sales of properties also can substantiate adjustments made to the selling prices. Re-sales from individual property owners, rather than from developers or subdividers, provide a better indication of typical market value. A separate sales ratio analysis should be performed using sale prices adjusted for financing compared to resold properties.

Results from these sales ratio studies can validate or reveal the inaccuracy of the adjusted sales data. Refer to Chapter 8, Statistical Measurements, for additional information on sales ratio and other statistical analysis techniques.

Adjustment for Time (Time Trending of Sales Data)

Most appraisal organizations, such as the Appraisal Institute (Institute) and the International Association of Assessing Officers (IAAO), recognize the need for time adjustment (trending) of sales prices to the date of appraisal.

The need for time trending is discussed in the Appraisal Institute’s reference text, The Appraisal of Real Estate, 2020, 15th Edition.

Market Conditions

Comparable sales that have occurred under different market conditions than those applicable to the subject on the effective date of the value estimate require adjustments for any differences that affect their values. A common adjustment for market conditions is made for differences occurring since the date of sale. Since the time the comparable sales were transacted, general values may have appreciated or depreciated due to inflation or deflation or to investor's changing perceptions of market conditions.

Although the adjustment for market conditions is often referred to as a time adjustment, time is not the cause of the adjustment. Market conditions that shift over time create the need for adjustment, not time itself. If market conditions have not changed, no adjustment is required even though considerable time may have elapsed.

In IAAO's text titled Property Appraisal and Assessment Administration, 1990, time adjustments are discussed.

Adjustments for Time

When price levels are changing significantly, sales prices must be adjusted for time. Separate time-adjustment factors by type of property and geographic area may be necessary, as rates of change in real estate prices often vary with these factors. The target date to which sales prices are adjusted should be the appraisal date.

The vacant land sales prices must be adjusted for time of sale to June 30th of the year preceding the year of change in level of value. This adjustment is mandatory for any length of sales data collection period used for sales analysis.

In the analysis of sales, time adjustments must always be made immediately following the deduction of personal property value included in the transaction and adjustments for financing, if any. This will establish a common reference point in time for the property characteristics adjustments.

Values tend to change unevenly depending on intended use and economic area. Because of this, time adjustments should be made within land use classes and within economic areas, if possible. When sales are scarce, the assessor must analyze the available sales in great detail to make an accurate adjustment for time.

Determination of market adjustments for time involves the use of one of the four basic techniques of time trend analysis:

- Paired Sales Analysis

- Property Re-sales Analysis

- Sales Ratio Trend Analysis

- Multiple Regression Analysis

Each of these techniques will be discussed individually in the paragraphs below. Each technique has specific advantages and disadvantages. The use of each method should be thoroughly reviewed, checked, and analyzed before any application is made to other properties.

Paired Sales Analysis

Paired sales analysis of closely comparable properties is based on the economic principles of Substitution and Contribution and the traditional sales comparison (market) approach to value. Closely comparable properties selling at different times are identified and the difference in sales prices is attributed to the effect of changes in market conditions (time).

If adjustments for physical differences between the properties are necessary, these adjustments are made before the difference due to time is measured. Adjustments for physical differences must reflect the contributory value of the difference at the time of the most recent sale.

The following data requirements are necessary to complete paired sales analysis:

- Two or more qualified/verified sales of comparable properties

At a minimum, the sales should be of the same property subclass, from the same neighborhood or economic area, and the same designated data collection period. If improved, the properties should have the same basic building design, a similar effective age, and have comparable square footages. - The date of sale for each sale including day, month, and year the transaction occurred

- Contributory value, at the time of the most recent sale, of any physical differences between the properties other than date of sale

The following steps should be used in the paired sales analysis trending factor calculation procedure:

- Collect two or more comparable properties, of the same subclass, within the same neighborhood or economic area. Adjustments have been made as appropriate for deduction of personal property value included in the transactions and for atypical financing as part of the confirmation and qualification/verification process.

- Make adjustments to the most current sales prices to account for any differences in the properties' physical characteristics. Adjustments for physical characteristics must reflect the contributory value of the differences in the property at the time of the most current sale.

- Array the adjusted sales from oldest date of sale to the most current date of sale.

- Determine a usable sales price per unit of comparison, e.g., sales price per square foot.

- Calculate the actual dollar per unit and percent change per unit between each sale.

- Divide the percentage change amount by the number of months between the sales. The resulting number is the rate of change in value for the time period between the two sales.

- Array the monthly percent change for each set of paired properties from low to high. Select the median percent change per month. The application of time adjustments, calculated by paired sales analysis, is described under the Application of Time Adjustments topic later in this section.

If it is suspected from analysis of economic area sales patterns and discussions with real estate professionals that the percent change per month is significantly different depending on the location of the property sold, different percent changes for each economic area can be calculated and applied. This approach is only reliable if a sufficient number of paired sales are used to determine the individual economic area percent changes.

The quantity and quality of sales analyzed should be extensively documented for use in valuation appeals and assessment performance analyses. An example of this technique is shown below.

Example:

Using a five-year data collection period, you were able to find four sales of properties with virtually identical physical characteristics, except for minor design and age differences. All sales were verified and adjusted, if necessary, to reflect the sales price of real property only. No financing adjustments were necessary. All sales were inspected at the time of sale.

| Parcel ID# | Sales Price | Date of Sale | Parcel Size | SP$ per sq ft |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3611-121-12-001 | $13,000 | 1/08 | 8,000 sq ft | $1.63 |

| 3611-121-15-002 | $10,500 | 7/10 | 7,200 sq ft | $1.46 |

| 3612-132-01-015 | $15,400 | 8/11 | 11,000 sq ft | $1.40 |

| 3614-122-05-016 | $12,400 | 5/12 | 9,100 sq ft | $1.36 |

Calculation of the time adjustment percentage is shown below.

-$0.17 difference between 2008 and 2010 divided by 2008 sales price and then divided by the number of months (30) between the two sales.

-0.17 ÷ 1.63 = -0.104 ÷ 30 mo. = -0.0035 per month

-$0.06 difference between 2010 and 2011 divided by 2010 sales price and then divided by the number of months (13) between the two sales.

-0.06 ÷ 1.46 = -0.041 ÷ 13 mo. = -0.0032 per month

-$0.04 difference between 2011 and 2012 divided by 2011 sales price and then divided by the number of months (9) between the two sales.

-0.04 ÷ 1.40 = -0.029 ÷ 9 mo. = -0.0032 per month

Note that the results from the property re-sales analysis indicates a percentage decrease, due to market conditions (time), ranging from -0.35 percent to -0.32 percent with a median of -0.32 percent. Based on the data range, a rounded median overall percentage decrease of 0.30 percent per month can be supported. In addition, since there were no sales occurring on or close to 6/30/12 in this example, the decreasing rate of decrease of 0.30 percent per month was assumed to extend to 6/30/12, the data collection trending point.

Advantages of Paired Sales Analysis

- In most counties, there generally are a sufficient number of closely comparable property sales that can be collected, qualified, verified, and used in this technique.

- Rates of change developed in this technique are relatively easy to understand and explain to taxpayers and judicial bodies.

Disadvantages of Paired Sales Analysis

- The county must accurately determine contributory value of any differences in physical characteristics between the properties that would contribute to the difference in sales prices.

- The threshold for what constitutes "closely" comparable sold properties must be set by the county prior to beginning the analysis.

- It is very difficult to reliably modify this analysis to account for nonlinear changes in value. Nonlinear changes in value are graphically represented by a curved line of best fit when sales price and date of sale are plotted on an x-y graph.

When using the property re-sales analysis to determine time adjustments, the assessor must ensure that a sufficient number of qualified/verified property re-sales are collected and analyzed to reliably measure the time trend rate of change throughout the data collection period. Comparison to time adjustments developed through sales ratio trend analysis is probably the best way to ensure reliability.

Property Re-sales Analysis

Property re-sales analysis involves analysis of two or more sales of the same property at different times. Two or more sales of the same property are identified and the difference in sales prices is attributed to the effect of changes in market conditions (time). An advantage of this technique is that possible differences due to location, design, and other physical characteristics are eliminated or reduced due to use of the same property.

If any other adjustments for changes to the property between dates of sale are necessary, these adjustments are made before the difference due to time is measured. Adjustments for differences in physical characteristics must reflect the contributory market value of the difference at the time of sale and are made to the more current resold prices.

The following data requirements are necessary to complete property re-sales analysis:

- Two or more, qualified/verified sales prices of the same property

- The date of sale for each sale including day, month, and year the transaction occurred

- Contributory market value, at the time of the more current sales, of any differences in physical characteristics in the property between dates of sale

The following steps should be used in the property re-sales analysis trending factor calculation procedure:

- Collect, qualify, and verify as many parcels as possible that have sold two or more times within the designated data collection period. Adjustments have been made as appropriate for deduction of personal property value included in the transactions and for atypical financing as part of the confirmation and qualification/verification process.

- Make any adjustment to the more current sales prices to account for any physical differences in the property between dates of sale. Adjustments for physical characteristics must reflect the contributory value of the difference at the time of sale.

- Array the adjusted sales prices from oldest date of sale to the most current date of sale.

- Determine a usable sales price per unit of comparison, e.g., sales price per square foot.

- Calculate the actual dollar change per unit and percent change per unit of comparison between each sale.

- Divide the percentage change amount by the number of months between the sales. The resulting number is the rate of change due to time for the time period between the two sales.

- Array the monthly percent change for each set of resold properties from low to high. Select the median percent change amount. The application of time adjustments, calculated by paired sales analysis, is described under the Application of Time Adjustments topic later in this section.

If it is suspected from analysis of economic area sales patterns and discussions with real estate professionals, that the percent change per month is significantly different depending on the location of the property sold, different percent changes for each economic area can be calculated and applied. This approach is only reliable if a sufficient number of paired sales are used to determine the individual economic area percent changes.

The quantity and quality of sales analyzed should be extensively documented for use in valuation appeals and assessment performance analyses.

An example of this technique applied to two sales each of three separate properties is shown below.

Example:

Using a five-year data collection period, you have found three properties that have sold twice within the data collection period. All sales were verified and adjusted, if necessary, to reflect the sales price of real property only. No financing adjustments were necessary. All sales were inspected at the time of sale and had not changed, other than for normal wear and tear, since the sale date.

| Property | Parcel ID# | Sales Price | Date of Sale |

|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | 4123-134-13-001 4123-134-13-001 | $67,000 $79,000 | 6/1/08 1/1/12 |

| #2 | 4123-134-15-005 4123-134-15-005 | $74,000 $80,000 | 7/1/09 3/1/11 |

| #3 | 4124-123-01-003 4124-123-01-003 | $49,000 $56,000 | 9/1/07 1/1/11 |

Calculation of the time adjustment percentage is shown below.

Property #1

$79,000 (1/1/12 sale) - $67,000 (6/1/08 sale) = $12,000 (43 months)

$12,000 ÷ $67,000 = 0.179 ÷ 43 mo. = +0.0042 (0.42 percent increase per month)

Property #2

$80,000 (3/1/11 sale) - $74,000 (7/1/09 sale) = $6,000 (20 months)

$6,000 ÷ $74,000 = 0.081 ÷ 20 mo. = +0.0041 (0.41 percent increase per month)

Property #3

$56,000 (1/1/11 sale) - $49,000 (9/1/07 sale) = $7,000 (40 months)

$7,000 ÷ $49,000 = 0.143 ÷ 40 mo. = +0.0036 (0.36 percent increase per month)

Note that the results from the property re-sales analysis indicate a percentage increase, due to market conditions (time), ranging from 0.36 percent to 0.42 percent with a median of 0.41 percent. Based on the data range, a rounded median overall percentage increase of 0.4 percent per month can be supported. In addition, since there were no sales occurring on or close to 6/30/12 in this example, the rate of increase of 0.4 percent per month was assumed to extend to 6/30/12, the data collection period trending point.

Advantages of Property Re-sales Analysis

- Rates of change developed from re-sales are relatively free from influences of other physical condition differences that might contribute to the difference in value between dates of sale. Unless the property has suffered excessive physical deterioration, has been extensively remodeled, or otherwise has changed between dates of sale, the difference in value is attributable to market conditions (time).

- Rates of change developed in this technique are relatively easy to understand and explain to taxpayers and judicial bodies.

Disadvantages of Property Re-sales Analysis

- Within the county, only a small number of re-sales may exist within the designated data collection period. This number may be even smaller or nonexistent for additional stratifications, e.g., economic areas.

- The county must accurately determine contributory value, at the time of sale, of physical differences between the dates of sale that would contribute to differences in the more recent sales prices.

- It is very difficult to modify this analysis to account for nonlinear changes in value. Nonlinear changes in value are graphically represented by a curved line of best fit when sales price and date of sale are plotted on an x-y graph.

When using the property re-sales analysis to determine time adjustments, the assessor must ensure that a sufficient number of qualified/verified property re-sales are collected and analyzed to reliably measure the time trend rate of change throughout the data collection period. Comparison to time adjustments developed through sales ratio trend analysis is probably the best way to ensure reliability.

Sales Ratio Trend Analysis

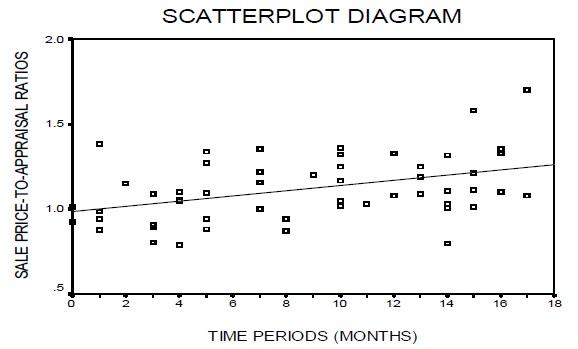

Sales ratio trend analysis is a market-based statistical method. It utilizes linear regression analysis to determine if time adjustments are indicated. The amount of adjustment, if any, can be calculated from the sales ratio trend analysis results. The objective of the analysis is to determine the percentage rate of change represented by the slope of the least squares trend line through the pattern of sales ratios over time.

Overall sales ratio trend analysis performed by property subclass is less precise than analysis completed by specific economic areas containing at least the recommended thirty sales needed for reliable statistical analyses. It is recommended that sale trend analysis by property subclass be undertaken only when there are insufficient numbers of sales by economic area.

For each reappraisal cycle, sales prices are adjusted to the appraisal date. When sale price-to-appraisal (S/A) ratios rather than appraisal-to-sale price (A/S) ratios are used in the analysis, an upward trend in the ratios indicates inflation; a downward trend indicates deflation. The direction and rate of change can be visualized by a line-of-best-fit drawn on a scatterplot diagram. For mass appraisal purposes, it is recommended that the rate of change be applied on a constant (straight-line) basis.

S/A ratios are plotted on the vertical (y) axis against time intervals on the horizontal (x) axis. A linear regression "line-of-best-fit" is drawn, and the slope of the line is calculated. The slope of the line will be one factor used to determine the rate of change in value per month attributable to time. The other factor will be the y-intercept, i.e., the place on the y-axis where the line-of-best-fit crosses.

In the following example, the analysis of a sample data set containing 54 sales ratios collected over an 18-month data collection period was completed. The S/A ratios are plotted against month of sale coded from 0 (oldest) to 17 (most recent). The results and a scatterplot diagram derived from the analysis follow:

Results of Sales Ratio Trend Analysis:

| No. of Observations | 54 |

|---|---|

| Sig T | 0.001 |

| Constant | 0.984 |

| X Coefficient | 0.0015 |

| No. of Observations = | The number of rows of data being analyzed in the data set |

|---|---|

| Sig T = | The significance of T statistic provides a measure of certainty as to whether the trend is valid and should be considered |

| Constant = | The y-axis intercept |

| X Coefficient = | The slope for each independent variable |

The Sig T Statistic is a statistical test that is used to evaluate the significance of a hypothesis. The hypothesis in time trending is that there is not a time trend. If the Sig T Statistic is less than 0.05, then the hypothesis is rejected and the time trend is deemed statistically significant. In other words, the appraiser can be ninety-five percent confident that a time trend should be applied. If the Sig T Statistic is between 0.05 and 0.10, the time trend is deemed “borderline” significant and other direct and indirect time trending techniques should be examined before deciding whether to apply a time trend adjustment. If the Sig T Statistic is greater than 0.10, the time trend is deemed insignificant and should not be applied.

The sales ratio trend analysis in the example utilizes non-weighted least squares regression of the base year S/A ratios over time. The regression formula calculates a mathematical trend from the ratios that is visually represented in the scatter plot diagram. Measurement of the degree of slope in the trend allows the calculation of the percentage rate of change per month or “time trend”. Since the Sig T is less than 0.05 for the property subclass, the time trend is deemed statistically significant and should be considered.

Calculation of rate of change is determined by applying the following formula:

X Coefficient (Slope) / Constant (Y Axis Intercept)

The resulting number is the rate of change per month (in decimal form) that can be used to time trend sales prices to the appraisal date.

Calculation of the time trend for the example data set is shown below:

X Coefficient / Constant = Rate of Change per Month

0.015 / 0.984 = 0.0152 or 1.52 percent increase per month

Advantages of Sales Ratio Trend Analysis

- There is less concern with stratification by property characteristics. A sales ratio reflects the relationship between the sales price and the value that exists for properties of different physical characteristics. However, stratification and analysis by subclass and location should be performed to determine if different time trends exist.

- Nonlinear (curved) rates of change can be determined using sales ratio trending. However, the methods used to determine and measure nonlinear rates of change are more complex than described here.

- Sales ratio trending is easily administered as a component of any sales confirmation program. The only data required are the previous value, sales price and sale date.

- Time trending factors determined from other trending techniques can be compared and analyzed to determine if the effect of time is accurately represented.

Disadvantages of Sales Ratio Trend Analysis

- The assessor's actual value for each sale must reflect the property characteristics for which the sales price was established.

- Another limitation to sales ratio trend analysis is the assumption that the previous year’s values reflect correct market values of the previous appraisal date.

- The distribution of sales ratios used in this analysis must be representative of properties within the analysis area. Additional analysis should be performed to ascertain the representativeness of the sales ratio trend analysis sample.

As a reminder, sales ratios used in the sales ratio analysis technique must be based on the existing actual values that have been determined for the prior general reappraisal cycle. For the reappraisal year, sales ratios should be calculated using the sales prices collected during the data collection period ending June 30 of the prior year, divided by the assessor's actual values reflecting the prior base period appraisal date.

Multiple Regression Analysis

Multiple regression analysis (MRA) is a technique for determining the influence of several independent factors, called independent variables, on a single dependent variable, usually the total market value of the property. Examples of independent variables are size in square feet, location, age, and other property characteristics.

If time of sale is one of the independent variables, its effect on market value can be estimated and an average rate of change in price levels can be extracted. For example consider the following MRA derived model.

MV (Market Value) = $10,909.93 + ($499.78 X months since sale) + ($43.10 X sq.ft.) + ($121.90 X location) + etc.

Here the independent variables include:

- Number of months since the sale occurred to the appraisal date (months since sale)

- Square footage of the property (sq.ft.)

- Location of the property (location) as a dummy variable

Each of these independent variables has a multiplier, called a coefficient. If the regression analysis determines a coefficient for number of months since sale of $499 and the average sale price is $100,000, then the average indicated rate of change is approximately 0.005 percent per month ($499 ÷ $100,000) or 6 percent per year (0.005 X 12).

It must be emphasized that this is simply an average indicated rate of change and that the actual rate of change in this model would vary from property to property depending upon the property's sale price or calculated market value. Also, this is a linear model in that every additional month from the appraisal date would add $499 to the calculated value.

More realistically, multiple regression can be used to develop nonlinear (curved) adjustments for time. And to improve accuracy of the resulting calculated market values, separate regression models can be built for different stratifications of property.

Development of MRA models is beyond the scope of these procedures. Please refer to Property Appraisal and Assessment Administration, IAAO, (1990) for additional information on MRA model building. Also recommended are IAAO Course 311 – Residential Modeling Concepts and Course 320 - Multiple Regression Analysis.

Advantages of MRA

- Regression allows for analysis of large amounts of data.

- This technique can easily manipulate data to test theories and hypotheses.

- Contributory values for many property characteristics can be tested. Those property characteristics that significantly influence value can be identified and their influence on value can be statistically verified.

- MRA can include nonlinear (curved) relationships within and between property characteristics.

Disadvantages of MRA

- MRA may produce unreliable results with small sample sizes.

- The technique is difficult to explain to taxpayers.

- To properly use all aspects of the technique requires knowledge of statistics.

- Time trends are not "decomposable", i.e., they cannot be separated from their interaction with other variables. Time trends extracted from MRA are best used as a comparison to trends developed from other time trend techniques and should not be exclusively applied outside the regression equation.

Application of Time Adjustments

Application of monthly time adjustments to sold property prices for paired sales, property resales, and sales ratio trend analysis determined monthly time adjustments are to be applied as shown in the following example.

Time adjustments should be applied to all confirmed sales using the following formula.

TASP = SP[1 + (rt)]

TASP = Time Adjusted Sales Price

SP = Sales Price

r = Time adjustment percentage decimal equivalent. This will be a negative number in a declining market.

T represents the number of months between the month of sale and the June 30th appraisal date.

In using the time adjustment technique, the assessor should be aware of the following:

- To achieve an accurate time adjustment estimate, all sales must be confirmed.

- When using two or more sales of the same property to establish time adjustments, the property must not have had any material physical change between dates of sale.

- All sale dates should be identified as occurring in the same month that the transaction occurred.

- All sales should be inspected at the time of sale to ascertain their physical characteristics.

As soon as confirmed land sales are adjusted for time, they should be plotted on land maps. Ideally, these maps would be the same maps on which zoning (land use) and economic area boundaries have been drawn. Assessors may prefer, however, to post land use and economic area boundaries on base maps and to post sales data on individual property maps that show land dimensions, shape and size.

Both the time adjusted sales price and the price per unit should be shown within the boundaries of the land sold. A standard unit price can then be developed for each street or block and shown on the land valuations map. This permits the assessor to note the location of sales and to detect price per unit patterns.

Information on making time adjustments can be found in the following publications:

- Property Appraisal and Assessment Administration, 1990, International Association of Assessing Officers.

- Property Assessment Valuation, 2010, International Association of Assessing Officers.

- Fundamentals of Mass Appraisal, 2011, International Association of Assessing Officers.

Adjustments for Differing Property Characteristics

Location Adjustments