In accordance with §§ 39-1-103(5) and 39-1-104(12.3)(a)(I), C.R.S., each Colorado county assessor is required to determine the “actual value” of taxable property located in their county on the January 1 assessment date each year. Colorado statutes define actual value as that value determined by appropriate consideration of the following approaches to value:

The assessor is to consider the approaches to value that are applicable to valuing the personal property prior to determining an actual value estimate as required by §§ 39-1-103(5) and 39- 1-104(12.3)(a)(I), C.R.S. If the taxpayer's declaration is complete; if it contains a full and complete disclosure of reasonable costs of acquisition, installation, sales/use tax, and freight to the point of use; and if it is timely filed, the cost approach to value is considered the maximum value as required by § 39-1-103(13), C.R.S. Reasonable costs are defined as costs that were available to any market participant at the time of the personal property acquisition. Reasonable costs can be estimated using costs declared for similar personal property from similar business/industry accounts. The costs of personal property acquired through special deals, special concessions, purchasing power based discounts and/or other transactions that were not available to the general public at the time of the personal property acquisition are not considered reasonable costs.

For Colorado personal property assessment purposes, § 39-1-104(12.3)(a)(I), C.R.S. requires that the actual value is the value in use. Colorado statutes also require that personal property be valued inclusive of all costs incurred in acquisition and installation of the property. The costs of acquisition, installation, sales/use tax, and freight to the point of use must be considered in the personal property valuation. The inclusion of these costs requires that personal property be valued in use. Therefore, the actual value of personal property is based on its value in use, as installed.

Appraisals are made to determine the value of personal property. An appraisal is an estimate of value as of a given date. The assessor estimates the value of the property being appraised by using comparative data consisting of cost, recent sales, and income information. The relationship between the subject property being appraised and similar properties of known value forms the foundation of the three approaches used to measure the value of personal property. Current actual value is established each and every year for personal property as required by §§ 39-1-104(12.3)(a)(I) and 105, C.R.S.

In Colorado, the assessment date for personal property is defined by § 39-1-105, C.R.S., as January 1 of each year. However, after a current value is established, it is rolled back to the June 30 appraisal date established for real property, using the factors found in Chapter 4, Personal Property Tables, as required by § 39-1-104(12.3)(a)(I), C.R.S. According to § 39- 5-108, C.R.S., the assessor values all taxable personal property owned by, in the possession of, or under the control of each taxpayer in the county based upon the characteristics and condition of the property as of January 1.

The assessor documents all valuations for assessment and maintains complete appraisal records to support the values placed on the personal property. The three approaches to value must be considered and documented on the appraisal records. If a given approach to value is not applicable, the assessor should note this in the appraisal records along with defensible reasons why the approach was not used, as prescribed in Montrose Properties, LTD et al. v. Colorado Board of Assessment Appeals et al., 738 P.2d 396 (Colo. App. 1987).

Data Collection and Analysis

Before estimating the value for personal property, the assessor gathers and analyzes all necessary data. The assessor gathers general, comparative, and specific data with which to complete the appraisal. Data is collected for the subject property (the property being appraised) as well as for comparable (similar properties). Most data collection occurs during the discovery process as discussed in Chapter 2, Discovery, Listing, and Classification.

General Data

Several types of general information are gathered by the assessor. The general information is useful in determining the economic environment that the personal property is used in and may provide clues as to the actual value of the property. The types of general information include the following:

- Economic Trends

- National

- Regional

- Local

- Specific Industry

- Business Cycles

- Governmental Regulations

Specific Data

The specific information necessary to value personal property includes the following:

- Current property owner’s name and mailing address

- Property location

- Property general use:

- Residential

- Commercial

- Industrial

- Agricultural

- Natural resources

- Property description

- Property acquisition year

- Property original installed costs

- Property specific use

- Property physical condition

- Property estimated remaining economic life

This information is specific to the subject property being appraised.

The primary tool used to gather specific information is the personal property declaration schedule.

The specific information includes a description of the subject property which is crucial to an accurate valuation. The assessor should obtain a clear, current, and detailed description of the subject property before estimating the value. Without an accurate description of the subject property it will be difficult for the assessor to gather comparable information.

As discussed in Chapter 1, Applicable Property Tax Laws, it is the duty of the taxpayer to furnish information to the assessor about the nature and condition of the property being appraised as required by §§ 39-5-107, 108, and 114, C.R.S. However, the assessor does have a responsibility to gather as much data as possible and to contact the taxpayer if in doubt as to the nature of the subject property.

Comparative Data

Comparative data is used to measure the value of the subject property by comparison with other, similar property. Necessary comparative data includes all specific data, as gathered for the subject. The degree of similarity between the comparable property data and the subject will determine the usefulness of the comparative data in making the appraisal.

Comparative data consists of cost, market, and income information and may be gathered for groups of taxable property.

Any comparative data gathered for use in the appraisal must be confirmed before use. It is especially important that sales information be verified with the buyers and sellers and income and expense data be verified with lessors and lessees. This will ensure that data used in the valuation of the subject is accurate. Cost data submitted by the taxpayer can be confirmed during an office review or a physical inspections. Data that cannot be verified should be used with caution in the appraisal of the subject property.

Highest and Best Use

Unless otherwise required by law, personal property should be valued according to its highest and best use. For personal property, “The highest and best use of an asset is generally when the asset is fully installed and operating for the purpose in which the asset was intended” (Standard on Valuation of Personal Property, IAAO, 2018). The value in use concept requires that personal property be valued inclusive of all costs incurred in the acquisition and installation of the property. As such, typically the highest and best use of personal property is consistent with its value in use.

Application of the Approaches

The assessor is to consider the three approaches to value in determining an actual value estimate for taxable personal property as required by §§ 39-1-103(5) and 104(12.3)(a)(I), C.R.S.

For Colorado personal property assessment purposes, § 39-1-104(12.3)(a)(I), C.R.S. requires that the actual value is the value in use. Colorado statutes also require that personal property be valued inclusive of all costs incurred in acquisition and installation of the property. The costs of acquisition, installation, sales/use tax, and freight to the point of use must be considered in the personal property valuation. The inclusion of these costs requires that personal property be valued in use. Therefore, the actual value of personal property is based on its value in use, as installed.

The most current valuation information available must be gathered and analyzed. It is Division policy that sales comparison (market) and income information used to determine the current actual value of all types of personal property should be gathered and analyzed from the twelvemonth period immediately preceding the current assessment date, i.e., the prior calendar year. Analysis of data from this period insures that adequate current market and income information is used in the valuation of personal property.

Assessors must document the physical condition of personal property as of the assessment date. Assessors also must consider current economic conditions when appraising personal property and must document the reasons for any functional and/or economic obsolescence that may exist as of the assessment date.

Cost Approach

The cost approach is based upon the principle that the value of a property equals the cost of acquiring an equally desirable substitute property. It is essentially an estimate of the cost of replacing the subject property with a new property that is equivalent in function and utility. However, the subject property is usually worth less than its cost of replacement because of depreciation.

Depreciation can be defined, in simple terms, as the loss in value due to any and all causes. However, cost tables only reflect physical depreciation due to ordinary use of the personal property and some functional obsolescence. The cost tables do not reflect depreciation due to extraordinary functional and/or any economic obsolescence, which must be separately estimated. Refer to Determine Accrued Depreciation later in this chapter.

Colorado statutes provide that the cost approach shall establish the maximum value of personal property when the owner of the property has timely filed a declaration which contains full and complete disclosure of all reasonable costs incurred in the acquisition and installation of the property as required by § 39-1-103(13)(a), C.R.S.

As paraphrased from § 39-1-103(13)(c), C.R.S., the assessor must consider the cost approach in good faith and shall not deny its use except for just cause that the owner has not made full and complete disclosure, or has not filed a declaration by the statutory deadline. Also, an assessor that wrongly denies the use of the cost approach can be held liable for all costs incurred by the taxpayer in protesting an assessment based on such denial.

Note that taxpayer declared costs that are not representative of reasonable costs at the appropriate retail “end user” level should not be used. Instead, comparable personal property costs should be researched and used in place of the unreasonable declared costs.

Types of Cost

There are several different cost bases that are referred to in accounting and appraisal work. The different types of cost and descriptions of each are as follows:

Reproduction Cost New

Reproduction cost new is defined as “The cost of reproducing a new replica of a property on the basis of current prices with the same or closely similar materials, as of a specific date” (Valuing Machinery and Equipment, ASA, 4th Edition, 2020).

Replacement Cost New

Replacement cost new is defined as “The current cost of a similar new property having the nearest equivalent utility as the property being appraised, as of a specific date” (Valuing Machinery and Equipment, ASA, 4th Edition, 2020).

RCN is an acronym that is used to represent either Reproduction Cost New or Replacement Cost New, whichever is appropriate. When using the cost approach, the appraiser must clearly denote the cost sources used and what RCN represents.

Manufacturer's Cost

Manufacturer's costs include only those costs that have been incurred by the manufacturer of the property to produce the property at the plant. The manufacturer's cost is not at the appropriate retail “end user” trade level and it does not include installation, sales/use tax, and freight to the point of use.

Original Installed Cost

Original installed cost is the amount that was paid for the personal property when it was new. Original installed cost includes the purchase price of the personal property, freight to the point of use, applicable sales/use tax and any installation charges necessary to ready the property for use in the business.

Original installed cost should be the cost declared on the personal property declaration schedule. It represents the cost to the owner for acquiring the personal property, putting it in place, and having it ready for its intended business use at the appropriate retail “end user” trade level. Original installed cost is not a depreciated value.

Original installed cost is synonymous with historical installed cost. Original installed cost is trended to estimate RCN as of the assessment date.

Cost to Current Owner

The cost to current owner is generally the depreciated acquisition cost of used personal property reported by subsequent owners. When the current owner has purchased used personal property, the costs reported on the declaration schedule filed by the current owner may represent the depreciated value of the personal property.

If the current owner of the personal property does not have the reasonable original installed cost information to report to the assessor, then the reasonable cost to current owner (depreciated costs), in use may be used. The costs reported by the current owner must represent reasonable used personal property acquisition costs. If not already included in the cost to current owner, an allowance for freight to the point of use, applicable sales/use tax and any installation charges necessary to ready the property for use in the business must be added. Note that taxpayer declared costs that are not representative of reasonable costs at the appropriate retail “end user” trade level should not be used. Instead, comparable personal property costs should be researched and used in place of the unreasonable declared costs.

Assuming that a current owner of personal property has timely filed a declaration that includes a full and complete disclosure of all costs incurred in the most recent acquisition of the property, the most recent sale price must be used as the acquisition cost prior to calculating RCN. The only exceptions to this rule are as follows:

- If the last transaction was not arm's-length, then prior acquisition costs or comparable RCN estimates from outside sources should be used. If the costs declared are not representative of reasonable costs at the appropriate retail “end user” trade level, then they should not be used.

- If the personal property is at the end of its economic life and the depreciated value floor of the personal property generally has been reached, then the acquisition price paid for the personal property is treated as the depreciated value floor (RCNLD) for the personal property and no RCN trending factors or percent good (depreciation) factors are applied to these prices unless the personal property is reconditioned or upgraded to extend its remaining economic life.

Even though personal property has been permanently taken out of service, but has not been scrapped or sold, it still has value. However, additional functional and/or economic obsolescence may exist.

Trade Level

Personal property valuation should consider the appropriate trade level, which refers to the production and distribution stages of a product. There are three distinct trade levels including: the manufacturing level, the wholesale level, and the retail “end user” level. Incremental costs will be added to the product cost as it advances from one level to the next. Therefore, the final product cost will differ depending on the level of trade. In light of the Colorado Constitutional provisions requiring property to be assessed at its “actual value” and promoting the principle of “equalized value,” for Colorado ad valorem taxation purposes, all property is valued at the retail “end user” level.

If an owner of taxable personal property declares manufacturing or wholesale costs, the county assessor should request an amended listing of personal property showing the original installed costs or the market-derived RCN at the appropriate retail “end user” trade level. In cases where the taxpayer provides declared costs that are not representative of reasonable costs at the appropriate retail “end user” trade level, the unrealistic declared costs should not be used. Instead, comparable personal property costs should be researched and used in place of the unreasonable declared costs.

In Xerox Corporation v. Board of County Commissioners of the County of Arapahoe, 87 P.3d 189(Colo. App. 2003), the Colorado Court of Appeals concluded that, “various ARL provisions bolster the conclusion that the comparable sales price, rather than the manufacturer’s cost, is the appropriate starting point for the cost approach under § 39-1-103(13).” It further stated, “the DPT’s interpretation comports with Colorado constitutional provisions requiring property to be assessed at its ‘actual value’ and promoting the principle of ‘equalized value.’”

Unique Personal Property

Occasionally, specialized industrial and other types of unique personal property are designed and manufactured within a company. In cases where the taxpayer has built a piece of personal property for which no comparables exist in the market, the taxpayer must estimate the cost of materials and labor used to build the personal property. In addition, estimates for freight to the point of use, installation charges, and sales/use tax must be added to develop a reasonable value in use for the personal property. The estimation procedure is to be used only when no comparable personal property exists in the market.

No or Low Cost Personal Property

Taxable personal property acquired for no or low monetary cost, to the owner (e.g., trades, gifts) still has value. The reasonable cost of comparable personal property; along with the reasonable costs of installation, sales/use tax, and freight to the point of use are to be used to develop a reasonable value in use for the personal property.

Antique Personal Property

Antique value is generally considered an intangible value component and should not be included in the valuation of personal property for property tax purposes. Market sales of antique personal property will typically exceed the RCNLD value. Antique personal property should be valued using the RCN of comparable non-antique personal property that serve the same purpose or function. In determining the RCN of antique personal property, the appraiser should consider the quality and other physical characteristics in determining the appropriate RCN.

Bulk Sale of Personal Property

When the sale of a business results in the transfer of most or all of the business's personal property to a new owner, this is known as a bulk sale of personal property. Provided that the sale is an arm's length transaction and the declared cost represents the reasonable value in use of the sold personal property, this sale of used personal property represents the acquisition cost to the new owner and may be used as the basis for the personal property value. Personal property bulk sale costs that are calculated based on an allocation may not be representative of a reasonable value in use for the personal property. Note that taxpayer declared costs that are not representative of reasonable value in use at the appropriate retail “end user” level should not be used. Instead, comparable personal property costs should be researched and used in place of the unreasonable declared costs.

For personal property which has reached its depreciated value floor by the date of acquisition, the reasonable value allocated from the bulk sale price is frozen. For personal property which has not reached its depreciated value floor, the value allocated from the bulk sale price is depreciated over a complete economic life appropriate to the personal property as though the personal property were new.

Cost Approach Procedure

The steps in the cost approach for personal property valuation are:

- Estimate RCN.

- Determine accrued depreciation.

- Calculate RCN Less Depreciation (RCNLD).

- Adjust RCNLD to the June 30 level of value established for real property.

Estimate Replacement or Reproduction Cost New

In the cost approach, the assessor determines either the cost of producing an exact replica of the subject property at current cost (Reproduction Cost New) or the cost of replacing the subject property with personal property that is similar in function and utility (Replacement Cost New). RCN is an acronym that is used to represent either Reproduction Cost New or Replacement Cost New, whichever is appropriate. When using the cost approach, the appraiser must clearly denote the cost sources used and what RCN represents.

The two methods used by assessors to estimate the RCN of personal property are:

- Original installed cost trended by cost indices

- Research RCN data from outside sources

Original Installed Cost Trended by Cost Index:

Original installed cost trending is the most commonly used method for estimating RCN in Colorado. The method relies on original installed costs furnished by the taxpayer and is applicable in a mass appraisal approach to valuing personal property.

The RCN is estimated for personal property appraisals by multiplying the original installed cost of the subject by the appropriate cost index factor for the year of acquisition. The index, or trending factor, adjusts the original installed cost to the current cost of replacing the personal property with similar personal property.

Price indices developed with the use of Marshall Valuation Service have been compiled and published by the Division for use by all assessors. These indices show the specific rates and directions of price movements throughout various industry categories. The base year for the Marshall Valuation Service indices is 1926. This means that the published factors are based upon 1926=100%. The indices measure the difference between 1926 costs and current year costs.

The Division of Property Taxation, through the courtesy of Marshall Valuation Service, converts the industry cost indices into cost trending factors. The factors relate original installed costs, by industry category, to current year costs. The factors are published annually so that assessors may use them to estimate the current RCN of personal property. The factors are found in Chapter 4, Personal Property Tables.

Original installed cost trending has several limitations:

- The cost factors are designed to be used only during the economic life of the property. After the property has reached the end of its economic life, the factoring of original installed costs may lead to distorted RCN values.

- As property ages, the use of original installed cost multiplied by trending factors and percent good factors may not yield reasonable RCNLD values. Any RCNLD estimate should be cross-checked with market and income information sources and adjusted, if necessary.

- The cost factors are based upon broad surveys of personal property cost levels conducted by the Marshall Valuation Service.

In the year in which the personal property has reached its minimum residual percent good floor, the applicable RCN trending factor in use at that time is "frozen" and the Level of Value (LOV) adjustment factor is “frozen” at 1.0. For the assessment years that follow, the RCNLD value does not change unless the personal property has been reconditioned or upgraded to extend its remaining economic life.

Even though personal property has been permanently taken out of service, but has not been scrapped or sold, it still has value. However, additional functional and/or economic obsolescence may exist.

The cost factors published in this manual are intended for use with original installed costs submitted by the taxpayer. Each category factor is industry specific.

Determination of Current RCN From Outside Sources:

The RCN of personal property is also estimated directly from market information published

by outside sources. Typical sources of RCN information include the following:

- General Services Administration (GSA) List Prices

- Manufacturer Catalog List Prices

- Reported Costs of Similar Property

- Local Cost Surveys of Equipment Dealers

- Commercial Replacement Cost Manuals

GSA List Prices

The GSA, or General Services Administration, is the central purchasing and leasing agency for the federal government. Many manufacturers publish catalogs specifically for use by the federal government. These catalogs contain current selling prices and lease rates available to federal agencies from individual manufacturers. These manufacturers must be contacted to obtain their GSA price lists. At the time of contact, the manufacturers should be queried as to whether discounts from the listed prices are typically given.

The assessor must also take care that the personal property listed in the price list are comparable to the subject property. In addition, estimates for freight to the point of use, installation charges, and sales/use tax must be added to develop a reasonable value in use basis for the property. The GSA prices are current RCN prices and should not be trended using cost factors found in Chapter 4, Personal Property Tables.

Pricing Catalogs

Many manufacturers or distributors of personal property maintain current pricing catalogs for the retail trade. Price catalogs are similar to the GSA prices in that they contain current replacement costs for various types of personal property. Price catalogs are available from the manufacturers or distributors of the property.

The price lists give information about the RCNs of certain personal property for the period of time in which the lists are valid. Supply catalogs such as J.C. Penney contain pricing information for common types of personal property.

The assessor must also take care that the personal property listed in the catalog or price list are comparable to the subject property. In addition, freight to the point of use, installation charges, and sales/use tax must be added to develop a reasonable value in use basis for the personal property valuation. Catalogs, which are current on January 1 of the assessment year, provide the best information. Any current prices taken from any catalogs should not be factored using the cost trending factors found in Chapter 4, Personal Property Tables.

Reported Costs of Similar Property

Assessors may review the reported costs of similar personal property from personal property declarations schedules to help them determine a reasonable cost at the appropriate retail “end user” trade level. Costs reported on the personal property declaration schedules should represent either the original installed cost or cost to current owner of the personal property. If the reported costs represent the original installed costs from other personal property schedules with similar personal property, the assessor can use the reported costs to estimate reasonable original installed costs for similar personal property. If the reported costs represent the cost to current owner of the personal property, the assessor must make sure that an allowance for freight to the point of use, applicable sales/use tax and any installation charges necessary to ready the property for use in the business have been added before they can use the costs in the valuation process to derive the appropriate personal property value in use.

If the costs derived from this analysis are current replacement costs, they should not be factored using the RCN trending factors found in Chapter 4, Personal Property Tables. However, if the costs are not current, they must be factored from the year of the comparable costs to the current assessment date. In this event, the year of the costs may or may not correspond to the taxpayer's year of acquisition. It is important that the assessor knows which information is in use and applies the correct trending and percent good (depreciation) factors.

Local Cost Surveys of Equipment Dealers

Assessors may also contact local equipment dealers to determine RCN. Local equipment dealers have current list prices available for various types of personal property. The assessor should contact these dealers and ask about the prices of certain types of personal property. This is especially useful as a check on the accuracy of reported costs and trended values. At the time of contact, the dealers should be queried as to whether discounts from the listed prices are typically given.

The assessor must ensure that the personal property listed by the dealers are comparable to the subject property. In addition, estimates for freight to the point of use, installation charges, and sales/use tax must be added.

Commercial Replacement Cost Manuals

Several companies publish pricing manuals for personal property. These manuals are updated periodically and provide information for the assessor to use, especially in cases where no other information is available.

Many of the companies charge a fee for the information contained in the manuals. However, payment of the fee usually entitles the purchaser to all updates or factors used in the manual. The manuals provide a valuable crosscheck for RCN estimates.

Do not factor the prices listed in the manuals using the cost trending factors found in Chapter 4, Personal Property Tables. Trending factors are furnished with the manual by the publisher in order to trend manual RCN's to the current assessment date. Since these trending factors are specifically intended for use with the particular manual, the manual user should not apply these factors to other manuals or to original costs declared by the taxpayer.

The assessor must ensure that comparable personal property that is used from the manuals is comparable to the subject property. In addition, estimates for freight to the point of use, installation charges, and sales/use tax must be added.

Determine Accrued Depreciation:

Accrued depreciation is the difference between the current RCN and the present value of the personal property as of the appraisal date. Depreciation may be defined as follows.

Depreciation is "Loss in value of an object, relative to its replacement cost, reproduction cost, or original cost, whatever the cause of the loss in value," according to Property Appraisal and Assessment Administration, IAAO, 1990, page 641.

The causes of accrued depreciation are divided into three categories:

- Physical Depreciation (deterioration)

- Wear and tear from use or from the elements

- Negligent care or inadequate maintenance

- Damage from moisture, breakage, or fire

- Functional Obsolescence

- Poor plan, design, or style

- Mechanical inadequacy or superadequacy

- Functional inadequacy or superadequacy due to size, style, age

- Technological innovation

- Changes in manufacturing techniques

- Changes in consumer tastes

- Economic Obsolescence

- Adverse economic conditions

- Passage of restrictive legislation

- Loss of material or labor sources

Physical depreciation and functional obsolescence relate to deficiencies within the property itself. Deficiencies may be classified as either curable or incurable. The deficiencies are curable if the cost to repair, replace, or correct them is economically feasible. This cost to cure is economically feasible if the cost is equal to or less than the additional income which would be generated by the property after the deficiencies have been cured. The deficiencies are incurable if they are physically or economically impractical to repair, replace, or correct.

Economic obsolescence is due to negative forces outside the property. This type of depreciation is seldom curable and is generally classified as incurable.

Losses in value due to functional or economic causes are not related to the actual age of the property, but rather to changing market forces that affect the property. Physical depreciation is related more to its economic life, i.e., its full life assuming normal maintenance, rather than the actual physical age of the personal property. Therefore accrued depreciation is based upon economic life rather than physical life.

Depreciation, as used in appraisal, differs from depreciation as used in accounting. Accounting depreciation can be defined as “the total accruals recorded on the books of the owner of property summarizing the systematic and periodic expenses charged toward amortizing the investment of limited-life property over its expected life” (Standard on Valuation of Personal Property, IAAO, 2018). Accountants are interested in income tax deduction justification or allocation of the investment made in the personal property to various income producing activities. In contrast, the assessor attempts to estimate the actual value of the personal property as of the appraisal date.

The assessor must consider and document all elements of physical depreciation and functional and economic obsolescence as of January 1 each year before placing a value on personal property.

Measure Incurable Physical Depreciation:

Physical depreciation which is due to ordinary use of the property is incurable because it is economically impractical to bring the property to its original condition when new each year. In order to measure incurable physical depreciation, the assessor determines the total economic life, the effective age, the remaining economic life, and the appropriate depreciation amount to apply to the subject property. Remaining economic life is the number of years remaining in the economic life of the personal property as of the appraisal date.

To make a supportable estimate of incurable physical depreciation, the assessor first determines the correct total economic life of the personal property being appraised.

Total economic life is the total period of time over which it is anticipated that personal property can be profitably used. It is described as the sum of the effective age and the remaining economic life. Total economic life is usually less than the physical life of the property. The Recommended Economic Life information in Chapter 4, Personal Property Tables, is provided to ensure uniformity in the estimation of total economic life.

The following are characteristics of personal property that have long, average, and short term economic lives:

Long-lived Personal Property:

The characteristics of long-lived personal property include:

- Relatively large investment in relation to the value of the unit produced

- Occurrence in the heavy manufacturing processes such as metal, sugar, oil, paper, cement, stone, and milling

- Infrequent changes in the process, product, style, or function of the property or the industry

- Durability, characterized by a steady output, efficient operation, and normal operating costs over its economic life

- Difficulty in moving due to the special foundation or structures necessary for operation

- Tied to the economic life of the structure in which it is housed

Average-lived Personal Property:

The characteristics of average-lived personal property include:

- Found commonly in business and industry

- Adaptability to change or technical advances

- Susceptibility to obsolescence in both style and function

- Ease of relocation (mobility)

Short-lived Personal Property:

The characteristics of short-lived personal property include:

- High rate of total wear relative to replacement cost

- Rapid accrual of obsolescence due to advances in technical improvements and capabilities

- Lack of adaptability

Estimate Effective Age

The effective age of personal property is the age of the property as indicated by its condition and utility. Personal property that is not properly maintained, is used more extensively than the average, or due to technological advancement has diminished utility, may have an effective age greater than the actual age of the property. Conversely, personal property in better than average condition may have an effective age that is less than the actual age of the property.

Effective age may be determined from the declaration schedule submitted by the taxpayer and physical inspection of the property. Physical inspections are necessary to determine the use and condition of the property.

Determine Remaining Economic Life

Remaining economic life expresses the period of time remaining over which the subject property will provide a net return to the owner. In other words, it is the period of time from the appraisal date to the time when the property only has salvage value or is scrapped.

Remaining economic life is calculated by subtracting the effective age from the total economic life estimate.

Calculate Incurable Physical Depreciation to Arrive at % Good

The amount of incurable physical depreciation is calculated using the percent good table found in Chapter 4, Personal Property Tables. The percentage allowed for incurable physical depreciation plus the percent good equals 100%.

The percent good table measures the remaining value of property at given points in time during the total economic life of the property. The tables found in Chapter 4, Personal Property Tables, generally measure loss in value attributable to typical physical depreciation, and functional/technological obsolescence.

The percent good table is designed to estimate RCNLD. The column headings represent the typical economic life expectancy of the personal property under consideration.

The procedure for using the percent good table is as follows:

- Estimate total economic life.

- Estimate effective age.

- Multiply RCN by the percent good listed in the table that corresponds to the effective age of the personal property and its total economic life.

Measure Curable Depreciation & Functional Obsolescence

Curable physical depreciation and curable functional obsolescence are generally measured using the cost to cure method, i.e., the cost of curing or repairing the additional depreciation or obsolescence. Keep in mind that curable depreciation and obsolescence must be economically practical to cure. The cost to cure the deficiency is subtracted from the RCNLD estimate as a loss in addition to incurable physical depreciation.

Measure Incurable Functional and Economic Obsolescence

Incurable functional and economic obsolescence can be estimated by capitalizing the loss of income due to whatever causes exist at the time of the appraisal (rent loss method), by estimating that loss using direct sales comparison in the market, or by using an inutility formula to measure decreased output or production.

The analysis and verification of increased operating costs, reduced economic income, or reduction in market value of a property provide the assessor with indicators that a depreciation or obsolescence adjustment, over and above that published in age-life depreciation tables or the Personal Property Tables, may be warranted.

The court ruled in Colorado & Utah Coal Co. v. Rorex, 149 Colo. 502, 369 P.2d 796 (1962),that if economic obsolescence exists, it must be acknowledged and deducted.

Measuring Overall Depreciation Through Capitalization of Loss:

The assessor, in some cases, may be able to estimate the typical net income producing capabilities of the personal property being appraised. Then the actual diminished net income, from all causes of depreciation, is measured.

This difference in net income is capitalized using an overall capitalization rate (OAR), if possible. Even if the capitalization rate is developed using the band of investment or summation techniques as described in published appraisal texts and in ARL Volume 3, Real Property Valuation Manual, Chapter 4, Valuation of Vacant Land Present Worth, it must include return of investment, return on investment, and an effective tax rate.

The resulting capitalized value of the income loss from all causes of depreciation is subtracted from the estimate of the capitalized value of the income determined for a comparable property when new. This approach can only be applied when income can accurately be attributed to a single piece of personal property, as with a mobile hot dog stand. When income must be allocated to various pieces of personal property, this approach loses credibility and generally is not appropriate.

Measuring Overall Depreciation Through Direct Sales Comparison:

The amount of diminished value from extraordinary functional and any economic obsolescence can be estimated using the direct sales comparison method. In using this method, the assessor estimates the value of property with the obsolescence using sales of comparable obsolete property. If the calculated RCNLD value of the property is greater than the value indicated by the sales of obsolete properties, this difference is an indication of the value loss due to extraordinary functional and any economic obsolescence.

The assessor can use the direct sales comparison method to set up percent loss in value norms for different classes of properties within specific business activity codes. A percent loss in value factor for extraordinary functional and any economic obsolescence may be developed for a class of property within a business activity code and deducted from the calculated RCNLD after application of the percent good factors from the Personal Property Tables. The general percent good factors published in the Personal Property Tables account for incurable physical and some functional obsolescence. See Chapter 4, Personal Property Tables, for more information.

Sales used to quantify extraordinary functional or economic obsolescence should be qualified and verified to ensure the sales are arm’s-length transactions and representative of the market. Refer to the Sales Comparison (Market) Approach section later in this chapter for more information on qualifying and verifying sales data.

Sales prices should be adjusted to reflect a value in use by adding all costs that would be incurred to acquire, transport, and install the property at its point of use. Sales prices should also reflect, or be properly adjusted to reflect, the retail “end user” trade level. Refer to the Trade Level section earlier in this chapter for more information.

Measuring Functional or Economic Obsolescence through Inutility:

Obsolescence can also be measured using an inutility adjustment. Inutility represents a decrease in production or output relative to a piece of equipment’s rated or design production capacity. Inutility can be caused by physical depreciation and/or functional or external obsolescence. Because of this, the assessor must ensure that the cause of the inutility has been properly identified to avoid a double deduction of depreciation.

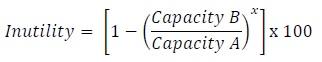

One method for calculating an inutility adjustment is that published by the American Society of Appraisers:1

Capacity A = Rated or Design Capacity

Capacity B = Actual Production

x = Exponent or Scale Factor

In general, the assessor should use actual production from the calendar year prior to the assessment date when determining the actual production (Capacity B) of the property for use in an inutility formula. It may also be appropriate to look at historic production to determine if long-term trends exist.

Rated or design capacity (Capacity A) can often be obtained from the manufacturer of the personal property. Caution must be exercised when using the manufacturer’s rated or design capacity in calculating an inutility adjustment. While rated or design production capacity may be appropriate in many instances, actual production may be less than rated or design capacity for reasons other than obsolescence. In some cases actual production may be less than rated or design capacity due to seasonality in production, downtime, repairs, planned growth in production, and other related factors. For instance, a manufacturer may operate at full capacity for a portion of the year but at a reduced rate for the remainder of the year. The apparent excess capacity is necessary to meet peak production and the property is not being underutilized due to obsolescence factors. In these instances, it may be inappropriate to apply an inutility adjustment, or the inutility calculation may need to be adjusted to account for these other causes of underutilization.

Underutilization of an asset does not necessarily demonstrate that obsolescence exists.

Decreases in production may also be attributable to other economic forces that may affect the business or going concern value of a business operation but do not affect the value of the personal property. As an example, a particular business may be failing to compete in a particular industry resulting in decreased demand for its products and decreased production. However, unless economic obsolescence exists in the industry as a whole, an inutility adjustment is likely unwarranted. The assessor must take care to differentiate economic obsolescence that may be affecting the value of the personal property from economic factors that may be affecting the business or going-concern value of the overall business operation.

Due to changes in market conditions and production numbers from year-to-year, inutility adjustments should be revalidated and re-quantified each assessment year.

The appropriate scale factor can be determined from published sources or can be calculated using a cost-to-capacity calculation. For more information on determining a scale factor using a cost-to-capacity methodology, please see Chapter 3, Valuing Machinery and Equipment, ASA, 4th Edition, 2020.

For more information on applying an inutility adjustment, see in Chapter 3 of the Valuing Machinery and Equipment: The Fundamentals of Appraising Machinery and Technical Assets, American Society of Appraisers (ASA), 4th Edition, 2020.

1 Valuing Machinery and Equipment: The Fundamentals of Appraising Machinery and Technical Assets, American Society of Appraisers (ASA), 4th Edition, 2020, page 69.

A complete discussion of the techniques and theories behind depreciation is found in Chapter 8 of the Property Appraisal and Assessment Administration, IAAO, 1990.

Calculate RCNLD:

The assessor deducts accrued depreciation from the estimate of RCN. The result is commonly called Replacement or Reproduction Cost New Less Depreciation (RCNLD). RCNLD reflects the current actual value in use of the personal property.

RCNLD, as calculated using the tables in Chapter 4, Personal Property Tables, includes loss in value from physical causes and is the indicated current actual value determined by the cost approach. Additional value loss due to extraordinary physical and functional obsolescence or any economic obsolescence can be deducted if these circumstances can be documented.

RCNLD must be factored to the June 30 level of value in effect for real property prior to applying the appropriate assessment percentage.

Valuation of Used Personal Property:

The valuation of used personal property requires that a decision be made concerning the remaining economic life of the property. If the personal property's elapsed age from its actual year of manufacture, or estimated effective year of manufacture, is equal to or greater than the number of years the personal property reaches its depreciated value floor, as evidenced in Chapter 4, Personal Property Tables, then the owner's acquisition cost for the personal property is to be treated as RCNLD and "frozen" at that value. The level of value will be frozen at 1.0 (LOV = 1.0) in the year that the personal property reaches its fully depreciated residual value.

An exception to this rule applies when the personal property is reconditioned to extend its remaining economic life. In such cases, the personal property’s effective age is adjusted appropriately and the reasonable acquisition, installation, sales/use tax, and transportation costs of the personal property are subject to depreciation over the entire estimated remaining economic life of the personal property.

Even though personal property has been permanently taken out of service, but has not been scrapped or sold, it still has value. However, additional functional and/or economic obsolescence may exist.

If, however, the elapsed age from the year of manufacture, or estimated effective year of manufacture, is less than the number of years when the personal property would have reached its depreciated value floor, as evidenced in Chapter 4, Personal Property Tables, then the property is treated as a new personal property and the owner's acquisition cost is subject to depreciation over the complete economic life of new personal property. The resulting value should be compared to comparable values in use of the personal property, if such information is available.

Sales Comparison (Market) Approach

In accordance with § 39-1-103(5)(a), C.R.S., the actual value of personal property must be determined by the appropriate consideration of the cost, sales comparison (market), and income approaches to value. However, § 39-1-103(13), C.R.S., specifies that the value derived from the cost approach shall be the maximum value if the owner has timely filed a declaration which contains a full and complete disclosure of all personal property including reasonable costs of acquisition, installation, sales/use tax, and freight to the point of use. The sales comparison (market) approach is based on independent information gathered by the assessor and may be considered when it results in a lower value than the cost approach as required by § 39-1-103(13)(c), C.R.S. The assessor may use the sales comparison (market) approach either when there is sufficient comparable sales data and the resulting value is lower than that indicated by the cost approach or when the declaration schedule contains faulty or misleading information.

The sales comparison (market) approach is based upon the assumption that property value may be measured by analyzing what buyers pay for similar property. There is one method that is typically employed in the sales comparison (market) approach to the valuation of personal property and that is the comparable sales method.

Comparable Sales Method

The comparable sales method involves analysis of market sales of comparable properties and possibly of the subject property itself. It provides an indication of what people in general are willing to pay for a given type of property at the time of sale, i.e., the market value of the property. Refer to the Bulk Sale of Personal Property under the topic Types of Cost and to Sources of Data under the Comparable Sales Method topic, both in this chapter.

The procedure for the direct sales comparison method is as follows:

Step 1 - Collect and confirm comparable sales data

Step 2 - Select appropriate units of comparison

Step 3 - Adjust comparable sales data using market data

Step 4 - Array and analyze the adjusted comparable sales data

Step 5 - Estimate the current actual value of the subject

Collect and Confirm Comparable Sales Data

Before the sales comparison (market) approach can be used on personal property, two conditions must exist:

- There must be personal property comparable or similar to the subject.

- Reliable sales data must exist for the comparables.

The assessor gathers current market sales for personal property being appraised. Current sales include transactions occurring during the twelve months preceding the assessment date. These transactions must include, in addition to acquisition price paid by the current owner, adjustments for the cost of installation, sales/use tax, and freight to the point of use.

In accordance with Jefferson County Board of County Commissioners v. IBM Credit Corporation, 888 P.2d 250 (Colo. 1995), all information that is provided to and/or gathered by the assessor up to the assessment date that may affect personal property valuation should be considered. In addition, current sales are gathered because §§ 39-1-103(5)(a) and 39-1- 104(12.3)(a)(I), C.R.S., require the estimation of current actual value of personal property before adjustment of that actual value to the June 30 appraisal date for real property.

Local, regional, state, or national sales data may be used. It may not be sufficient, when gathering market sales for personal property, to restrict the marketplace to an individual town or county. The personal property market is unique in that personal property is movable and has use in many locations. The assessor should attempt to obtain and analyze data from wherever the market exists for the personal property.

After sales of comparable properties have been gathered, the assessor must confirm them to ascertain whether or not they are arm's-length transactions. Confirmation should be made in writing, if possible, and may be accomplished through the buyer, the seller, personal property dealers, auctioneers, or brokers.

Verified sales should be given more weight than those sales where confirmation was initiated, but no verification could be acquired. It is important that the assessor note how the sales information was verified and how familiar the person was with the property.

Minimum Standards for Sales Data:

The following are the minimum requirements for the sales data used in the sales comparison

(market) approach:

- Date of sale

- Sale Price

- Condition of the sold property

- Age of the sold property

- Location of the sale

- Buyers' and sellers' names and addresses

- Special terms of the sale, if any

- Complete description of the sold property

- Any unusual conditions surrounding the sale

All of the information must be considered together as part of the valuation of the subject property.

Sources of Data:

There are several sources of comparable market data. The first source is the taxpayer. The acquisition cost of the property may provide the assessor with reliable market information for the date when the personal property was first acquired. Other taxpayers with similar property can provide market information for the same type of personal property. Once a database has been established, the assessor analyzes it to see if any trends emerge which indicate the actual value of the subject property. This analysis is useful for all types of property similar to the property in the database.

For personal property that, due to supply and demand imbalance, is oversupplied in the market, obsolescence is frequently reflected in auction sales prices. This is true only when auctions are the market for this personal property, i.e., when there are few, if any, resales of such personal property outside of an auction environment. Auction sales of personal property may provide reasonable value estimates provided that auctions are held to sell personal property in the normal course of the trade. If these transactions do not include installation, sales/use tax, and freight to the point of use, in addition to acquisition price paid by the current owner, adjustments to the value for the personal property must be made to develop a reasonable value in use.

Auction sales resulting from seller financial duress or involuntary liquidation of personal property are used only in rare instances where no other sales exist or when no other sales have taken place in the recent past. Bankruptcy or forced liquidation auctions may only give evidence of liquidation value instead of actual value. The assessor is appraising property at value in use not at liquidation value.

Used personal property guides may indicate the market value of used personal property. Since some guides report values for disassembled, non-installed properties, the assessor must determine if the used values include installation, sales/use tax, and freight to the point of use. If these transactions do not include installation, sales/use tax, and freight to the point of use, in addition to acquisition price paid by the current owner, adjustments to the reported value for this personal property must be made to develop a reasonable value in use.

Documentation as to the methodology used in determining the used personal property values and the sources for this data should be requested before considering the value as an indication of market value. The comparability of the property listed in the personal property guide to the subject property also must be determined.

Select Appropriate Units of Comparison

The assessor determines an appropriate unit of comparison for the subject and the comparable properties. Personal property units of comparison may include the following:

- Model number

- Equipment type and production output per time period

- Capacity and special accessory items

- Horsepower

- Weight

Any meaningful unit of comparison may be used so long as it allows the assessor to analyze subject and comparable properties on the same basis. Discussions with personal property manufacturers, personal property dealers, and personal property leasing companies may clarify the appropriate units of comparison.

Adjust Comparable Sales Data Using Market Data

Before adjusting sales, any differences between comparable properties and the subject property must be identified. The adjustment process accounts for differences between properties so that the comparable market data is made more similar to the subject. Types of adjustments which may be required are as follows:

- Financial terms of the sale

- Time of sale

- Location of sale

- Physical characteristics of the property (including capacity)

- Condition of the property

- Brand name

- Extra accessory items

Based on the effects of the market, there may be no adjustment for a specific difference. The assessor must investigate the marketplace to determine which differences in the property actually affect value.

Adjustments are always made to the comparable property sales prices and never to the subject.

Adjustments may be made in one of two ways:

- Percentage amounts

- Dollar amounts

Percentage Adjustments:

A percentage adjustment is made by adjusting the sales prices of other comparable properties by specified percentages of the sales price. The actual percentages used are derived from the market. Comparable property sales which are superior to the subject must be adjusted downward and comparable property sales which are inferior to the subject must be adjusted upward. Time adjustments, if applicable, must be made first because all sales must be on an equivalent basis before other adjustments can be made.

Example: Assume Property A recently sold for $20,000. The market indicates Property B, the Property you are appraising (Property B), sells for 20 percent more than Property A because it is in better condition. Using only this information, what would be your estimate of Property B's value?

Answer: $20,000 + (.20 X $20,000) = $24,000

Example: Assume Property A recently sold for $20,000. The market indicates Property A is ten percent better than Property B because Property A is in better condition. Using only this information, what would be your estimate of Property B's value?

Answer: $20,000 - (.10 X $20,000) = $18,000

Percentage adjustments may be determined by studying economic trends, price level changes, information from personal property manufacturers and dealers, or from the database of sales collected by the county assessor. Analysis of sufficient data should yield percentage value changes that may be applied to comparable property sales prices to estimate subject property value.

Dollar Adjustments:

Dollar adjustments are made in the same way as percentage adjustments except that actual dollar amounts are used. The amount of the adjustment is determined from the market.

Example: Assume Property A recently was sold for $20,000. The market indicates Property B, which you are appraising, sells for $4,000 more than Property A because it is in better condition. Using only this information, what would be your estimate of Property B's value?

Answer: $20,000 + $4,000 = $24,000

Note the similarity of the methodologies used in the two examples. The estimated value of the subject in both cases is the same.

The type of adjustments that should be made will depend on the data available and the judgment of the assessor.

A step-by-step example of the comparable sales method for the valuation of personal property is shown below.

Step 1 - Collect and Confirm Comparable Sales Data

Market data is collected, confirmed, and arrayed according to type of personal property, age, date of sale, and by units of comparison that may exist. An array is a grouping of data in a specific order that facilitates analysis in such a way that comparisons and relationships between the data may be identified and quantified.

Step 2 - Select Appropriate Units of Comparison

From this point the sales data are analyzed and market comparisons are made. The array facilitates analysis by displaying the data in a form that can quickly be sorted and analyzed.

The value ranges per unit of comparison that are established are ultimately used to establish indicators of market value.

Step 3 - Adjust Comparable Sales Data Using Market Data

Sales prices adjusted for installation, sales/use tax, and freight to the point of use, if necessary, are used in the arrays to establish value ranges for various types of personal property.

Step 4 - Array/Analyze the Adjusted Comparable Sales

The price paid for each unit of comparison can be calculated by dividing the sales price by the applicable unit of comparison. A range of values per unit emerges.

Step 5 - Estimate the Current Actual Value of Subject

From the data, a conclusion must be reached on the typical price per unit of comparison for the type of personal property. This analysis must be performed yearly to keep the market indicators current.

After the current estimated value of the subject has been determined, the assessor makes adjustments for installation, sales/use tax, and the cost of freight to the point of use, if these were not included with the acquisition price paid by the current owner to develop a reasonable value in use. The assessor's judgment and experience are involved in analyzing the values to estimate the final value. The value of the subject property must be reasonable, defensible, and documented.

Market indicators are used in the valuation of similar types of property for the current assessment year. Market indicators also provide a tool which can be used in checking cost approach depreciation estimates. And, they can be used for comparison with the value estimates developed using the cost and income approaches to value before a final value estimate is made. Market indicators can be especially useful with properties subject to a high degree of functional or economic obsolescence.

Income Approach

Colorado Revised Statutes section 39-1-103(5)(a), requires that the actual value of personal property be determined by appropriate consideration of the cost approach, the sales comparison (market) approach and the income approach. However, § 39-1-103(13), C.R.S., specifies that the value derived from the cost approach shall be the maximum value if the owner has timely filed a declaration which contains a full and complete disclosure of all personal property, including the reasonable costs of acquisition, installation, sales/use tax, and freight to the point of use. The income approach is based on independent information gathered by the assessor and may be considered when it results in a lower value than the cost approach as required by § 39- 1-103(13)(c), C.R.S.

Income analysis yields an estimate of the present value of future net benefits to be derived from a property. This approach is based on the premise that the price paid for property is dependent on the future net benefits to be derived or investors' estimates of what those future net benefits will be. The procedure for the income approach is as follows:

- Estimate gross income.

- Deduct allowable expenses to calculate net income.

- Determine capitalization rate or gross rent multiplier.

- Capitalize net income into value.

Estimate Gross Income

In using the income approach, the assessor first measures the economic income (rental or lease amounts) for comparable properties. Economic rental data can be gathered from actual rental data observed in the market. In cases where no rental rates can be established, it is very difficult to accurately value property using the income approach.

The assessor estimates the gross economic income for the property being appraised by gathering current rental or lease information from the books and records of taxpayers leasing or renting personal property.

The assessor also contacts personal property dealers or lessors to determine typical rental or lease rates for various types of personal property. The assessor measures gross income to the personal property, not to the business enterprise, and it must be clear that the income stream being measured is attributable only to the specific personal property.

In situations where the income stream is attributable to the entire business enterprise, including income for land, improvements, intangibles, and personal property, the assessor cannot allocate the income to the various components before attempting to value the personal property. The income attributable to the personal property must be capable of being isolated or the income approach should not be used to value the personal property.

The following terms are described in The Dictionary of Real Estate Appraisal, Appraisal Institute, 7th Edition, 2022:

- Rent - "An amount paid for the use of land, improvements, or a capital good."

- Profit - "The amount by which the proceeds of a transaction exceed its cost.

Comment: The income approach requires that the assessor only estimate the income attributable to the property being appraised, not to the entire business. Indeed, a business can operate at a loss instead of a profit, but this does not mean that the property used by the business has a negative value. The income measured by the assessor is the income attributable to the personal property, not business income. Therefore, the term profit is not used as a measure of the value of personal property. - Contract Rent - "The actual rental income specified in a lease."

- Economic Rent - "In appraisal practice, a term sometimes used as a synonym for market rent."

Comment: Economic rent, in appraisal, is a term sometimes used as a synonym for market rent. Economic rent is sought in the income approach because it is the rent justified for the property on the basis of comparable rental properties and upon past, present, and projected future rents of the subject property. It is customarily stated on an annual basis. - Gross Income - "Total income from a property before deducting any expenses, customarily stated on an annual basis. This means the gross income that could be generated by the property on an annual basis."

Comment: It is based on the economic rent determined from the analysis of rental rates of similar personal property, not the actual contract rent generated by the subject property.

Deduct Allowable Expenses to Calculate Net Income

The assessor deducts current, typical, personal property operating expenses from the gross income to estimate net income. The expenses deducted from the gross income must be typical for the type of property being appraised. The following expenses are generally allowable.

- Management

- Salaries

- Repairs and maintenance

- Insurance (if provided by the lessor)

There are other expenses that are not allowable expenses for deduction from gross income. These include the following:

- Depreciation

- Debt service

- Income taxes

- Capital improvements & expenditures

- Owner's business expenses

A complete discussion of the income approach is found in Chapter 5 of the Valuing Machinery and Equipment: The Fundamentals of Appraising Machinery and Technical Assets, American Society of Appraisers (ASA), 4th Edition, 2020.

After the assessor deducts the allowable expenses from gross income, the result is the estimate of net income. It is this estimate of net income that is capitalized into value. The net income is one of the critical components in the income approach to value. The other critical component is determination of the capitalization rate.

Determine Capitalization Rate

There are several methods used to determine capitalization rates. The data used in developing capitalization rates directly from the market include current typical income and expense data and market sales data. Data used in developing capitalization rates using other techniques include the rates of return expected by typical investors and by lenders, rates developed for recapture of the original investment, and effective tax rates. The techniques for the determination of the capitalization rate are fully discussed in the Chapter 12 of Property Appraisal and Assessment Administration, IAAO, 1990 and additional income approach information may be found in Chapter 5 of Valuing Machinery and Equipment: The Fundamentals of Appraising Machinery and Technical Assets, ASA, 4th Edition, 2020. Generally, the appropriate overall rate for personal property is higher than the overall rate for real property because of the short life of personal property.

Capitalize Net Income into an Indication of Value

There are three fundamental elements in the income approach: the personal property value (V), the net income from the personal property (I), and the rate of return on the investment (R). The relationship of these three quantities is expressed in three formulas, which are really three different arrangements of the same formula:

Formula 1: V x R = I

Formula 2: I ÷ V = R

Formula 3: I ÷ R = V

"V" and "I" are expressed in dollars. "R" is usually expressed as a percent, but in computations it should always be converted to decimal form. If the rate of return is 12 percent, it should be expressed as 0.12 for use in computations.

Example:

- If the property value is $50,000 and the capitalization rate is 12 percent, what is the net income?

Answer: $6,000 (formula 1: $50,000 x 0.12 = $6,000).

- If net income is $20,000 and the property value is $100,000, what is the rate?

Answer: 20% (formula 2: $20,000/$100,000 = 0.20)

- If net income is $18,000 and the overall rate is 15 percent, what is the property value?

Answer: $120,000 (formula 3: $18,000/0.15 = $120,000)

If any two of the three quantities V, I, or R are known, the third value can be determined by using the appropriate formula.

The actual value of personal property in the income approach is estimated by dividing the net income by the capitalization rate. The result is the estimate of actual value for the current assessment year. The following formula that is used to accomplish this was mentioned earlier in this chapter.

Formula 3: I ÷ R = V

or Income divided by the Capitalization Rate equals Value

The estimate of value from the income approach must include an allowance for the cost of freight to the point of use, installation, and sales/use tax, or adjustments for these costs must be made to develop a reasonable value in use.

Finally, the estimate of value from the income approach is adjusted to the level of value in effect for real property using the adjustment factor found in Chapter 4, Personal Property Tables.

Final Estimate of Value

After the assessor has determined the indicators of value from the applicable approaches, the current actual value must be determined and carried through to final assessed value. The abundance, reliability, and relevance of the available data will help determine which approach is the most appropriate to use to determine a reasonable value in use for the personal property.

The step in the appraisal process wherein the assessor determines the current actual value is called reconciliation.

Reconciliation

The actual value is determined using that estimate which can most readily be defended under the Colorado Revised Statutes. The reconciliation of all available valuation data will indicate which approach to value should be used for an individual property.

When the value indications from the three approaches have been determined, a reconciliation is made. Typically the value indications from the three approaches will not be the same. The best value estimate must be judged according to the following:

- Requirements of the Colorado Constitution, Colorado Revised Statutes, relevant case law, and the Assessors’ Reference Library manuals

- The amount and reliability of the data considered in each approach

- The strengths and weaknesses of each approach

- The relevancy of each approach to the subject property

For Colorado personal property assessment purposes, the actual value is the value in use, as installed. Colorado statutes require that personal property be valued inclusive of all costs incurred in acquisition and installation of the property. The costs of acquisition, installation, sales/use tax, and freight to the point of use must be considered in the personal property valuation. The inclusion of these costs requires that personal property be valued in use. Therefore, the actual value of personal property is based on its value in use.

As previously indicated, § 39-1-103(13), C.R.S., provides that the value derived from the cost approach shall be the maximum value of the personal property if the owner has filed a timely declaration which contains full and complete disclosure pertaining to the valuation of the property. Once these conditions have been met, values derived from the market and income approaches can be considered, but can only be used if they result in a lower value than the value estimated from the cost approach.

It is not acceptable to average value indications. Rather, the assessor relies upon the data that are superior in quality, quantity, and defensibility. If the data collected and analyzed do not support a reasonable estimate of value, the assessor must re-evaluate some or all of the appraisal data before a final estimate of value is made.

The final estimate of value usually is based upon taxpayer-submitted information. Under certain circumstances, the final value estimate may be based upon the “Best Information Available” (BIA). After establishing the actual value for the personal property as of the assessment date, the level of value adjustment factor must be applied to trend the personal property actual value back to the level of value in effect for real property as required by § 39- 1-104(12.3)(a)(I), C.R.S. Refer to Chapter 4, Personal Property Tables. After establishing the current value in use of the personal property as of the January 1 assessment date, the applicable level of value adjustment factor must be applied to trend the personal property value back to the applicable June 30 of the prior even year’s value.

Best Information Available Valuation

The assessor must value all taxable personal property even though no information has been received from the taxpayer. Failure by the assessor to receive a declaration schedule does not invalidate the assessor's valuation, § 39-5-118, C.R.S. Any valuation made without the receipt of the declaration schedule is known as a "Best Information Available" (BIA) valuation. Any valuation determined by BIA generally is not capable of adjustment through the abatement process. In Property Tax Administrator v. Production Geophysical et al., 860 P. 2d 514 (Colo. 1993), abatements for BIA values in excess of what should have been reported, had the taxpayer filed a declaration schedule, were disallowed.

BIA valuations are also made in cases where the owner of the property cannot be determined after due diligence. The assessor may list such property on the tax roll as “owner unknown” as permitted by § 39-5-102(2), C.R.S.

Taxpayers are always notified when a BIA valuation is made. Usually BIA valuations are made prior to the June 15 Notice of Valuation (NOV) deadline. Only in the case of omitted property can a BIA valuation be made after June 15. The assessor uses the Special Notice of Valuation (SNOV) and allows the taxpayer 30 days in which to protest such omitted property valuations. During the protest of any BIA valuation, the assessor should require the taxpayer to submit the personal property declaration schedule or an itemized listing of personal property for the year being protested. If the taxpayer refuses to submit the schedule or list, the protest is denied.

If the taxpayer owns personal property in excess of $52,000 in total actual value per county and does not file a property declaration schedule by the April 15th deadline or if the taxpayer requests either a 10 or 20 day filing extension, and fails to meet the extended deadline, the assessor makes a BIA valuation and adds a late filing penalty as required by § 39-5-116, C.R.S. Taxpayers owning personal property of $52,000 or less in total actual value per county are not required to file personal property declaration schedules, as this property is exempt from property taxation pursuant to § 39-3-119.5, C.R.S.